Until 22 July

KEHINDE WILEY: HAVANA

KEHINDE WILEY: HAVANA

APRIL 28 - JUNE 10, 2023

APRIL 28 - JUNE 10, 2023

April/May 2023

This spring, friends, aides, and decades’ worth of artworks traveled from across the globe to convene in New York for Wangechi Mutu’s momentous survey at the New Museum.

For years, LGDR has been a driving force in the art market. Now, the creative family is making a home for itself at one of the most historic addresses on New York’s Upper East Side.

This April, Daniel Lind-Ramos takes his monumental assemblage works to MoMA PS1 for his largest exhibition to date.

Ciaran McGuigan is bringing his homegrown family design business—and the perception of Irish craftsmanship—into the 21st century.

In the midst of a historic blizzard, Amy Adams braved the elements to dig out her snowed-in Portland gallery, inviting beloved artists and collaborators to celebrate Adams and Ollman’s 10th anniversary.

Ten years after Rachel Cargle left her marriage, she ruminates on the life she left behind, and the strength and conviction that allowed her to pursue the one she wanted.

In Shanghai, “Gucci Cosmos” brings the Italian fashion house’s rich history to life through an exhibition curated by Maria Luisa Frisa and designed by Es Devlin.

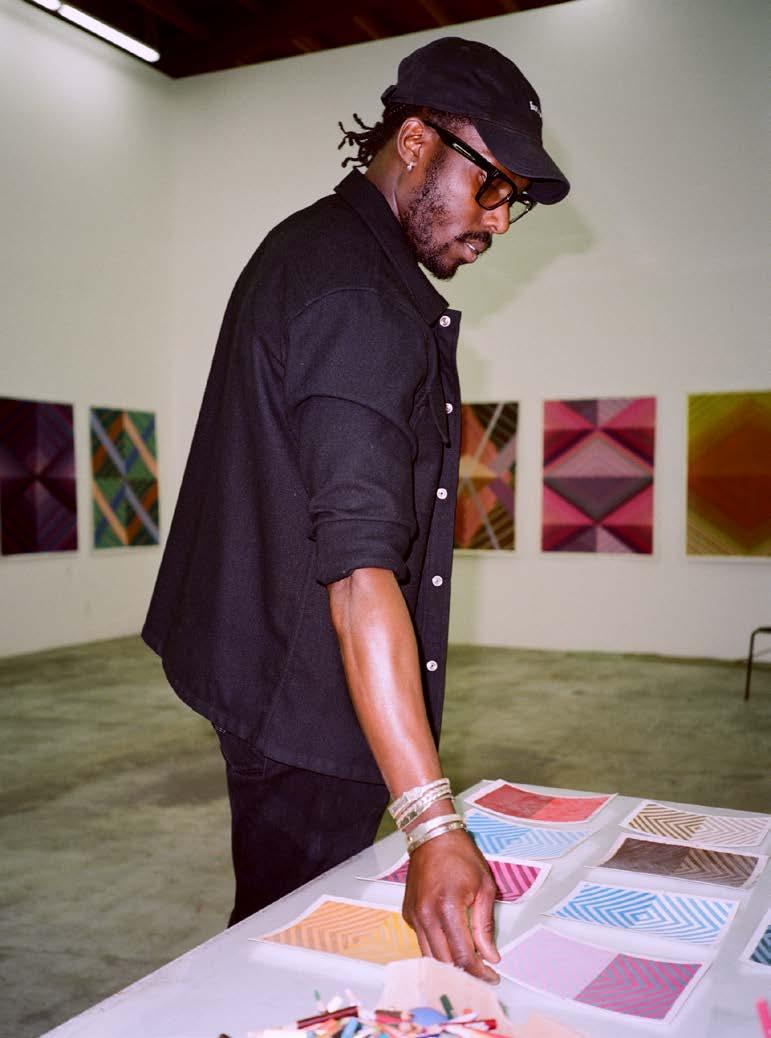

Brooklin Soumahoro likens his works to bursts of lightning, an apt descriptor for an artist who pours every ounce of his energy onto his canvas.

72

Misha Kahn harnesses advanced technology to envision his whimsical furniture designs, a number of which are on view at Friedman Benda in Los Angeles this spring.

74

Multidisciplinary art collective Moved by the Motion uses movement, music, and installation to unearth the hidden narratives buried in the Western literary canon.

April/May 2023

In the face of threats and censorship, Russian collective Chto Delat wages an unrelenting battle to protect freedom of speech in its home country.

SEAN, THOMAS, AND LAUREN KELLY

With Sean Kelly’s two children joining him as partners, the family gallery expands across the country.

PENNY PILKINGTON, WENDY OLSOFF, AND EDEN DEERING

Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington founded PPOW to create a space for underrepresented artists. Olsoff ’s daughter, Eden Deering, became part of the team in 2018, joining the ranks of women that she grew up admiring.

LUCY MITCHELL-INNES AND DAVID AND JOSEPHINE NASH

Lucy Mitchell-Innes and David Nash have shaped their gallery program into one of the most respected in the city. Now they’re expanding their contemporary program with help from their daughter, Josephine Nash.

84

Influenced by the adventurous work of her father, the Neo-Expressionist painter, Chiara Clemente has followed her own winding path to filmmaking.

88

PETER AND SALLY SAUL GET ALONG QUITE WELL

The rebellious painter and subversive sculptor share a studio in their compound in upstate New York, where each serves as the other’s muse and champion.

92

PIERRE

In the years since Pierre Paulin passed, a triumvirate of loved ones—the designer’s wife, Maïa WodzislawskaPaulin; son, Benjamin Paulin; and daughter-in-law, Alice Lemoine—have extended and redefined his legacy for a new century.

96

Chanel’s Métiers d’art is an annual celebration of craft and creative encounters. For this year’s collection, artistic director Virginie Viard unveils a historic merging of French design and West African tradition, all made by hand.

102

Doron Langberg doesn’t aim to shock. Rather, the artist’s fleshy, figurative oil paintings of explicit love-making scenes reverberate with passion, luring us in with raw emotion and sensuality.

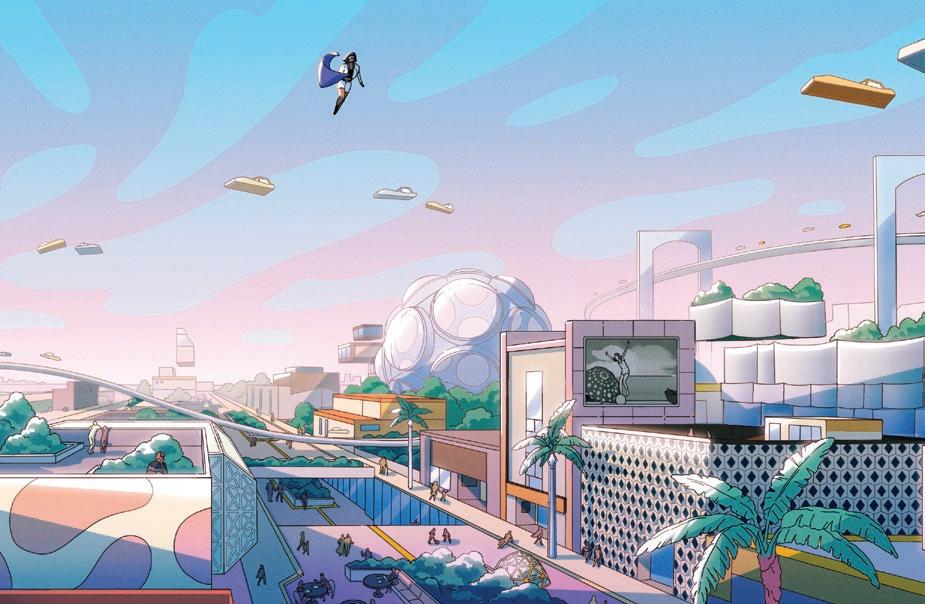

Artificial intelligence-generated artwork featuring Louis Vuitton Spring/Summer 2023. Artwork by David King Reuben.

108

PARENTING SHOULD BE LIKE PAINTING

When Emily Ratajkowski was around the age that her son, Sly, is now, she often found herself under the care of her father, the painter and sculptor John David Ratajkowski. On the eve of Sly’s second birthday, Emily and John reflect on the art of child rearing.

COLLECTING FOR THE FUTURE

In the era of the multi-hyphenate, CULTURED ’s sixth annual class of Young Collectors spotlights art lovers who are guided by their instincts and trust in their communities.

THE TIES THAT BRUISE US ALSO BIND

When Seán Hewitt published All Down Darkness Wide last summer, he found himself grappling with the ghosts of his own past—and with the legacy of trauma in queer literary history.

THREE GENERATIONS AT THE TABLE

Alice Waters and her daughter, Fanny Singer, host a family reunion of sorts over a meal made from fresh local ingredients, with the family’s youngest member—Fanny’s own daughter, Cecily Singer—at the center of the action.

120 136 142 148

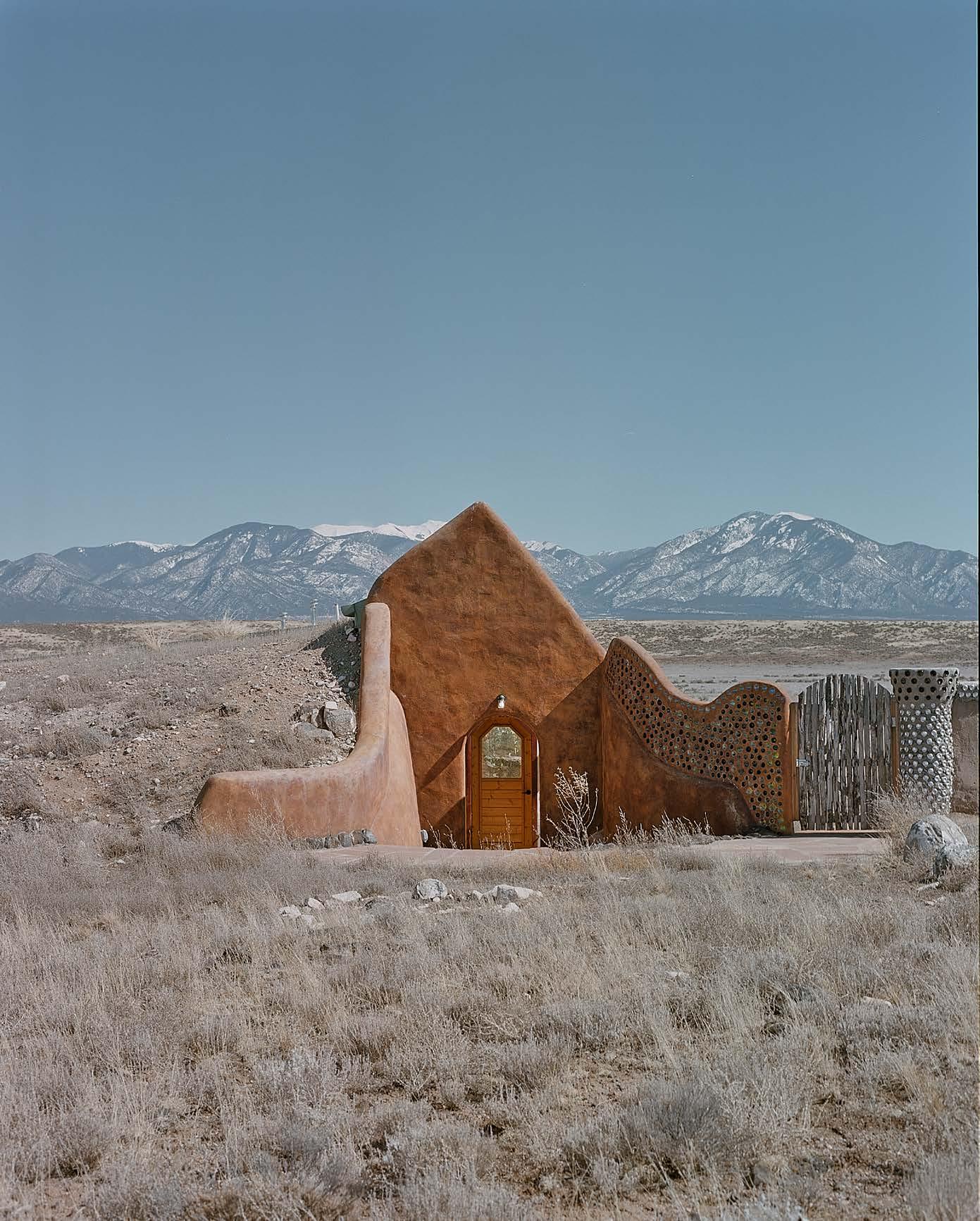

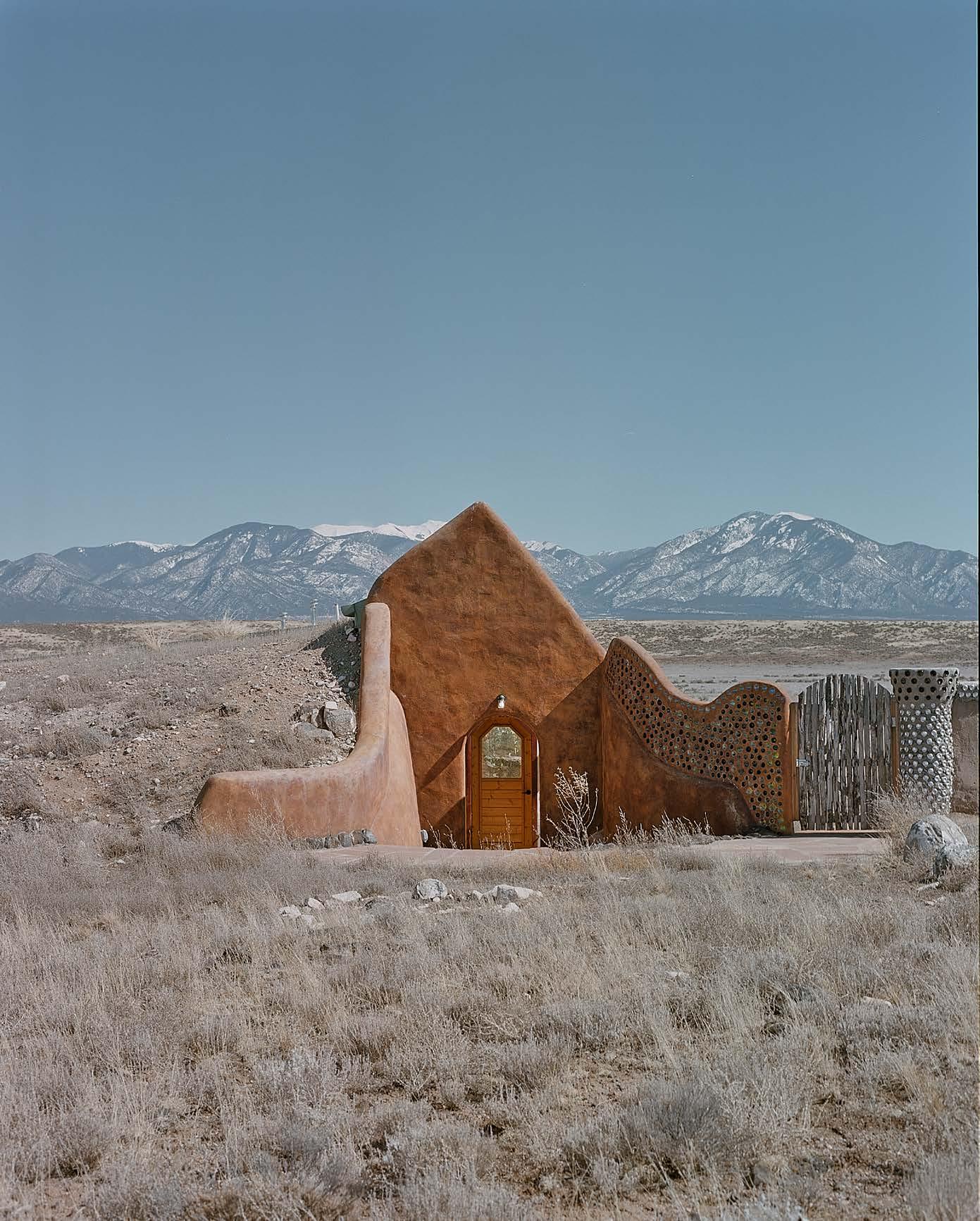

YOU LIVE WHERE?

In secluded colonies tucked into the American Southwest, colorful Earthship communities repurpose ancient building practices and recycled materials into passive structures powered by the sun and wind. These off-thegrid compounds offer us clues about how to live in a changing world. Welcome to Earthship Way.

160

WE MAKE BEAUTIFUL THINGS. THEN WE SET THE WORLD ON FIRE.

David King Reuben uses cutting-edge A.I. technology to create new worlds, dressing computer-generated models in sleek, decadent clothes from Louis Vuitton’s Spring/Summer 2023 Ready-to-Wear collection.

Elaine Sciolino is a Paris-based contributing writer and former Paris bureau chief for The New York Times. She is currently writing her sixth book, which is about “falling in love with the Louvre.” Says Sciolino: “For the past decade, Benjamin Paulin, Alice Lemoine, and Maïa WodzislawskaPaulin have formed the trio behind the family business Paulin, Paulin, Paulin. Their aim is simple: shed new light on the works of late French designer Pierre Paulin. I met them at their Paris house, an architectural gem which also serves as their showroom and headquarters.”

Pakistani-born and New York-based Salman

Toor’s sumptuous and insightful gurative paintings depict intimate quotidian moments in the lives of ctional young, brown, queer men ensconced in contemporary cosmopolitan culture. His work oscillates between heartening and harrowing, seductive and poignant, inviting and eerie. A solo presentation of Toor’s work, “No Ordinary Love,” is on view at the Tampa Museum of Art until June 2023. He is the recipient of a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, and his work is in the permanent collections of the Tate, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, among others. The artist contributes a series of previously unseen sketches in this issue that accompany Seán Hewitt’s meditation on the role of trauma in queer literature.

Jeanne Vaccaro is a writer and curator. Her book in process, Handmade: feelings and textures of transgender, explores the labor of crafting an identity and was awarded the Arts Writers Grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation. Vaccaro is an assistant professor of Transgender Studies and Museum Studies at the University of Kansas, and co-founder of the New York City Trans Oral History Project. For this issue, she considers the nature of collective art-making. “Artist collaborations possess a commitment to practice and to ritual that remakes the everyday as a site of possibility and change,” says Vaccaro.

The Instagram of Paris-born photographer Sam Hellmann is brimming with portraits of friends and celebrities like Bella Hadid and Oscar Isaac. Hellmann began her career as a photographer on movie sets before expanding into writing, directing, portraiture, and fashion work. In this issue, she turns her lens to the Paulin family. “It’s always a strange and interesting exercise to take someone’s portrait in their home,” Hellmann says. “It felt as if everything was aligned in perfect balance between the space and the people living in it. Even the children drawing in the kitchen were so peaceful and quiet; it was only at the end of the shoot that I realized they were there.”

Sean Davidson’s work documents interior architecture and contemporary design within commercial, personal, and institutional contexts. For this issue, Davidson travels to Taos, New Mexico, to explore the sustainable architecture practices of Earthship communities. “It seems like the future is always found out in the desert,” says the photographer. “Earthships seek equilibrium with the land and gaze up toward the stars to nd their power. The quietness of the land makes this an incredible place to hang out and photograph.”

Multidisciplinary artist David King Reuben works out of London on pieces that interrogate religion, God, and human beliefs, a re ection of his ultra-orthodox upbringing and eventual divergence from these teachings. This year, he will release a conceptual album accompanied by hundreds of hand-drawn, animated stills and an immersive live performance. Recently, Reuben has also delved into the world of arti cial intelligence. In this issue, he blends this cutting-edge technology with designs from Louis Vuitton’s Spring/ Summer 2023 collection. “Innovation is the ultimate disrupter of industries,” says the artist, “and as we’ve seen with the likes of Airbnb and Uber, no sector is safe from transformation. While I do not claim to have taken down the fashion industry, it is undeniable that the winds of change are blowing in its direction.”

Made

by people who design, craft and live. Handmade with love in Italy to last generations, since 1912.

poltronafrau.com

Scan to activate the augmented reality experience.

Bolero Ravel table and Montera chair designed by Roberto Lazzeroni

Bolero Ravel table and Montera chair designed by Roberto Lazzeroni

Seán Hewitt is a Dublin-based writer and literary critic. His memoir, All Down Darkness Wide, won the 2022 Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, and his poetry collection, Tongues of Fire, won the Laurel Prize in 2021. This year, his book of new versions of queer tales from Greek and Roman classics, 300,000 Kisses, will be released with Clarkson Potter. For this issue, he investigates the cultural politics of queer trauma in literature. “Maybe writers gift us some more time in the furnace, and a hand to hold ours while we are there, and perhaps that reformation is the place where queer happiness, where queer liberation, comes to life,” says the writer.

Los Angeles and Toronto-based Dominique Clayton has a host of job titles: writer, curator, dealer, founder, and contributing editor for CULTURED. The Columbia University and SCAD graduate founded her eponymous gallery and art advisory to serve as an incubator for emerging artists— particularly those of color and women. She has held positions at Lee Daniels Entertainment, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, The Broad, Jeffrey Deitch, and WACO Theater Center’s Wearable Art Gala. In this issue, Clayton speaks to Brooklin Soumahoro, a self-taught French painter with an expressive body of work.

Gregory Halpern and Ahndraya Parlato are photography professors at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Together, the husband and wife have published nearly 10 books of their work. The pair, a family in their own right, collaborated to photograph Emily Ratajkowski and her son, Sly, in their Manhattan home for this issue’s cover story.

Founder | Editor-in-Chief

SARAH G. HARRELSON

Executive Editor

JOSHUA GLASS

Senior Editor

MARA VEITCH

Senior Creative Producer

REBECCA AARON

Fashion Directors

ALEXANDRA CRONAN, KATE FOLEY

Editor-at-Large

KAT HERRIMAN

New York Contributing Arts Editor

JACOBA URIST

Associate Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Editorial Assistant

SOPHIE LEE

Contributing Art Directors

MAFALDA KAHANE, ORIANA REN

Contributing Columnist

RACHEL CARGLE

Podcast Editor

SIENNA FEKETE

Landscape Editor

LILY KWONG

Contributing Editors

FRANKLIN SIRMANS, SARAH ARISON, LAURA DE GUNZBURG, DOUG

MEYER, CASEY FREMONT, ALLISON BERG, MICHAEL REYNOLDS, DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

Publisher

LORI WARRINER

Italian Representative—Design

CARLO FIORUCCI

Marketing and Publishing Coordinator

HANNAH TACHER

Copy Editor

MEKA BOYLE

Interns

ANA ALTCHEK

ANNIE LYALL SLAUGHTER

SARAH WETSMAN

YAROSLAVA BONDAR

Prepress/Print Production

PETE JACATY

Senior Photo Retoucher

BERT MOO-YOUNG

CULTURED Magazine 2341 Michigan Ave Santa Monica, California 90404

TO SUBSCRIBE , visit culturedmag.com. FOR ADVERTISING information, please email info@culturedmag.com. Follow us on INSTAGRAM @cultured_mag.

ISSN 2638-7611

FOR OUR SECOND ISSUE OF THE YEAR, we set out to make sense of that messy, magnificent thing we call family. It’s an idea so big, so ever-changing, and so profoundly personal that it was difficult to pinpoint exactly where to begin. We quickly realized that, if you look for it, our families—the ones we choose, the ones we are stuck with, and the ones that form out of circumstance—play an enormous role in our stories. We decided to focus on those fundamental moments where a group of people, related or not, transform into more than the sum of their parts. Some of the relationships spotlighted in this issue have blossomed over decades—like the artists Peter and Sally Saul, who have been together for 50 years, or Alice Waters and her daughter Fanny Singer, a new mother herself. Others were born out of that elusive combination of trust and creative synergy—such as Wu Tsang’s collective, Moved by the Motion, a transdisciplinary and transcontinental art group working across film, music, and art. We wanted to give you an intimate glimpse into these complex and layered relationships, and we wanted to go deep—which is easier said than done.

Naturally, this journey begins with our cover star, Emily Ratajkowski. In all that she does, the actor, author, and entrepreneur is unafraid to speak her mind on the issues that matter to her—from motherhood to consent to creative ownership. Like many of us, Emily has become fascinated with the unexpected ways that her earliest experiences continue to inform the most essential aspects of herself. In an honest and affectionate conversation with her father, the artist John David Ratajkowski, Emily revisits a childhood spent inventing and exploring worlds while being both a student and collaborator in her father’s studio attached to their family home. Now, as a new mother, Emily is focused on offering the same experiences to her son. Her genuine interest in the power of human connection gives us a window into the engine of her success.

This issue also features our sixth annual Young

Sarah G. Harrelson Founder and Editor-in-Chief @sarahgharrelson

Follow us | @cultured_mag

Collectors list, a major undertaking that I am very passionate about. Every year, I spend a great deal of time talking with trusted friends to bring together a cohort of people who are using their privilege and platforms in thoughtful ways. We visited all 11 collectors in their homes, taking their portraits in front of the works that mean the most to them. Kat Herriman, CULTURED’s editorat-large, spent time with each of them, diving deep into their very personal collecting habits, the values that drive their acquisitions, and their unique philosophies of patronage. We hope their stories inspire you to support artists in any way you can. In the end, that is CULTURED’s mission.

As always, a big thank you to my dedicated team. I hope you have as much fun reading these pages as we did putting them together.

A report by Art Basel & UBS. Launching April 4.

AS WANGECHI MUTU ZOOMED WITH ME from her sunset-lit Nairobi studio earlier this spring, her team in New York, where it was still morning, was at work preparing for the KenyanAmerican artist’s then-upcoming show at the New Museum. One aide made wrinkles in Mutu’s sculptural fabrics; another gouged gallery walls with what the artist calls “wall wounds.” In a matter of days, the artist would join these friends, some of whom had come back to work with her after 20 years, for a gathering she describes as a family reunion. The metaphor could also be applied to her works—as we spoke, Mutu’s paintings, collages, videos, and sculptures were traveling from across the world to convene in the museum and make themselves at home.

Mutu, 50, achieved international acclaim in the early 2000s for her lavish collage admixtures of the mythic and mundane—crouching pinup models with crocodile tails and women pinning serpents with their stiletto heels. These “otherworldly superhero beings,” she imagined, “could redeem us from our bullshit and our small-minded problems that hurt us so tremendously.” Upon securing U.S. citizenship in 2015, she began dividing her time between Nairobi and New York. “Intertwined” (curated by Vivian Crockett, Margot Norton, and Ian Wallace) traces the connections, in terms of place as well as aesthetics, in Mutu’s practice over decades. In the show, the heroines of her mid-2000s collages—their bodies mottled with disease or decorative camouflage— acquire movement in the animated video The End of Eating Everything, 2013, and a third dimension through sculptures including The Glider, 2021, a soil-and-charcoal serpent goddess with holes for scales.

Mutu’s work has long addressed gendered violence and colonialism, but her historical imagination also tilts beyond history and toward millennia—an expansive perspective from which, she says, “our tribalisms completely dissolve.” Her sculptures, while governed by the same logic of accretion as her collages, seem more assured of their place in the world. She makes her clay from the soil in Nairobi, which she bakes in the sun, and adorns her sculptures with natural materials she has gathered from the land: moth wings, quartz, driftwood, bleached skeletons of sea animals. “To be drawn to these materials, to be able to recognize their beauty,” says Mutu, “that is my prayer.”

BY EMILY LORDI PHOTOGRAPHY BY KHADIJA M. FARAHThis spring, friends, aides, and decades’ worth of artworks traveled from across the globe to convene in New York for “Intertwined,” Wangechi Mutu’s momentous survey at the New Museum.Wangechi Mutu alongside her sculptural works in her studio in Nairobi, Kenya.

For years, LGDR has been a driving force in the art market, embracing the synergy and contradiction sparked by the diverse expertise of its founders Dominique Lévy, Brett Gorvy, Amalia Dayan, and Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn. Now, the creative family is making a home for itself at one of the most historic addresses on New York’s Upper East Side.

BY SOPHIE LEEIN ANOTHER LIFE, the walls of New York’s 19 East 64th Street mansion were adorned with the likes of Sandro Botticelli, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, and Rembrandt. The limestone-fronted edifice was completed in 1932 by Gilded Age architect Horace Trumbauer to house the private art dealership Wildenstein & Company, with adornments and arch windows inspired by the 18th-century Parisian Hôtel de Wailly. Now, LGDR will continue the building’s intimate entanglement with the arts by establishing its flagship gallery in the Upper East Side townhouse.

The Wildenstein family of art dealers hosted Old Master and Impressionist exhibitions at 19 East 64th Street for more than half a century before converting it into a private residence in the 1990s, with 11 members of the family bouncing between its five floors. Harry Brooks, the dealership’s former president, used to jokingly refer to it as the “most expensive tenement in Manhattan.” Indeed, when the Wildensteins finally sold the building to an anonymous buyer for $79.5 million in 2017, the sale set the record for the highest price ever paid for a Manhattan townhouse.

(The building broke the record again a year later when it sold for $90 million.) The grand home changed hands a few more times in the following years before LGDR acquired it in 2022 and set to work restoring its interiors in collaboration with architect and designer Bill Katz and HS2 Architecture.

To inaugurate its new flagship, the gallery has organized a transhistorical exhibition that marries the townhouse’s roots with its new, forward-facing raison d’être. “Rear View”— an exhibition of nearly 40 paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and photographs of the human figure from behind—opens this month and runs through June 3. Throughout its two floors of exhibition space, 20th-century masterworks by René Magritte and Francis Bacon enter dialogue with pieces by living artists such as Fernando Botero and John Currin, along with new commissions from artists including Francesco Clemente, Diane Dal-Pra, Urs Fischer, and Eric Fischl. The exhibition shines a light on the enduring resonance of the human posterior in figurative work, encouraging viewers to examine the past as well as what’s to come.

LEGEND HAS IT THAT LOÍZA, a small town that sits on the northeastern coast of Puerto Rico, takes its appellation from a Taíno kasike, or tribal chieftain, called Yuiza. She changed her name to the more Spanish-sounding Luisa after marrying Pedro Mejías, an Afro-Spanish conquistador who accompanied the first wave of European colonizers in the 1500s. Over the next five centuries, her geographical namesake would witness the arrival of Yoruba tribe members brought to Puerto Rico as enslaved Africans, the birth of the bomba and plena musical traditions, and the loss of hundreds of lives and homes to Hurricane Maria.

Daniel Lind-Ramos was born in Loíza 70 years ago to a family of seamstresses, carpenters, and mask-makers. Throughout his decades-spanning practice, the assemblage sculptor has made work from, about, and for the place where he grew up and still lives, the island’s unofficial capital of Afro-Puerto Rican culture. Using found and gifted objects— palm fronds, rusty pickaxes, blue FEMA tarps, and DVD players—he constructs monumental figures that trace the traditions, tales, and traumas of Afro-descendant communities in Puerto Rico and beyond. “Even though the works are inspired by Loíza, and Loíza is the filter through which I experience life, I am sure these experiences are shared by humanity,” the artist says. “For me, objects are charged with experiences, whether they’re personal or collective. That is what interests me in my work: how memories manifest through them.”

This spring, MoMA PS1 will present “Daniel LindRamos: El Viejo Griot—Una historia de todos nosotros,” the artist’s largest exhibition to date. The show will weave together long-standing and recent themes in Lind-Ramos’s practice through a presentation of 10 large-scale works. These include Centinelas de la luna negra, 2022-23, and El Viejo Griot, 2022-23. The first is a meditation on mangroves and their role as buffers to persistent erosion in a changing climate, and the latter refers to an “elder storyteller,” a character in the Fiestas de Santiago Apóstol, a celebration that takes place in Loíza each summer. Through the exhibition, the artist uses sculpture as a means for storytelling, refiguring rhythms past and present, and reflecting humanity in all of its textures.

Daniel Lind-Ramos brings his monumental assemblages— expressive containers of memories rooted in the Afro-descendant communities of Puerto Rico and beyond—to MoMA PS1 this spring for his largest exhibition to date.

WITH THE EXCEPTION OF THE FANCIFUL ROMANTICISM of fashion designers John Rocha and his daughter Simone Rocha, Irish design typically conjures images of lace, harps, and Celtic wood carvings. “It’s been attached to craft and diddly diddly diddly,” says Ciaran McGuigan, the creative director of his family business, Orior, “and I want to stay well clear of that.”

The brand was born after McGuigan’s parents, Brian and Rosie McGuigan, spent time in Denmark in the 1970s gaining exposure to furniture and design. When the pair returned to Ireland at the end of the decade, they vowed to bridge the gap between their new knowledge of Scandinavian aesthetics and their Irish heritage, founding Orior in Newry, Northern Ireland. More than 40 years later, the design operation is still very much a family affair. In addition to Brian, Rosie, and Ciaran, Katie Ann McGuigan— Ciaran’s younger sister and a London-based fashion designer—also contributes her eye to Orior, advising on creative direction and designing prints for the brand.

As a teenager, McGuigan landed stateside after earning a soccer scholarship at the Savannah

College of Art and Design. It wasn’t long before he realized that SCAD was more of a design mecca than a sports one—and perhaps not the best place for him at the time. When he was given the opportunity to play professionally in Sweden, he quickly hopped on a plane back to Europe. Eventually, he returned to the noted art school to play soccer (and also complete his film degree). When he graduated in 2014, McGuigan decamped to New York to expand the family business—which by then had evolved from a small local outfit to a full-fledged international operation. In 2022, Orior opened a 4,500-square-foot flagship in New York’s SoHo neighborhood which serves as a portal into the brand’s ethos.

Despite all of McGuigan’s innovations, though, quality and craftsmanship remain the backbone of every Orior piece. The company uses the finest textiles, leather hides, marble, and glass procured from purveyors across Ireland. The marble and lime-stone come from stonemasons S McConnell & Sons in Kilkeel, Northern Ireland. “We get the blocks from all over the place, and then we cut them in the size we need,” explains one artisan. Orior’s crystal tabletops

come from world-renowned glass sculptor Eoin Turner in Cork, Southern Ireland. Each piece is made-to-order; no two tables, chairs, or credenzas are exactly alike.

All this to say: every Orior piece is a work of luxury. The brand’s round Marmar table is made from a single marble slab, a Brutalist form that incorporates Orior’s trademark curves. Its Easca coffee table combines teardrop-shaped Irish green marble legs with a curved tabletop made from fine Irish crystal, and the Atlanta sofa’s sloping arms are complemented by a fringe-trimmed bottom. The Bianca chair, which resembles a plump pair of lips atop walnut legs, looks at home in any curated interior.

“We’re going to put Ireland on the map for design and furniture,” McGuigan asserts, and he’s certainly off to a good start. Orior has a cult following of notables—from Jon Gray and Maggie Gyllenhaal to Kelly Behun—and has collaborated with McGuigan’s fellow SCAD alum Christopher John Rogers on a capsule collection of chairs that fuse the fashion designer’s vibrant palette with four of Orior’s signature chairs. For followers of Ireland’s design evolution, the future looks bright.

BY ANN BINLOTCiaran McGuigan is bringing his homegrown family design business—and the perception of Irish craftsmanship—into the 21st century.

THIS PAST FEBRUARY, PORTLAND, OREGON saw its heaviest snowfall since 1943. The record-setting blizzard arrived the same week as two other local milestones: the 10th anniversary of Adams and Ollman, one of the city’s most influential art galleries, and the 50th birthday of its owner, Amy Adams. These factors swirled together one Saturday afternoon as friends and fans braved the icy conditions for the gallery’s celebratory exhibition. Prior to the opening, Adams cleared the space’s snow-covered sidewalk wear-ing a polka-dotted Balenciaga party dress, metal shovel in hand.

The gallerist is a tireless advocate and cheerleader for her artists, qualities she attributes to her mentor, John Ollman. The owner of Philadelphia’s legendary Fleisher/Ollman gallery is known for a nationally resonant program that spotlights the self-taught. Relationships are at the heart of Ollman’s business, a value he instilled in Adams, who runs her gallery more like a household than a money-making endeavor. “We always sold to a lot of artists because they were looking at art that wasn’t part of the mainstream for inspiration,” Adams says. “Artists have always been my favorite people to sell to, and over the years, that network has grown to include curators and more traditional collectors, too.” Jasmin Tsou of JTT gallery and gallerist and critic William Pym also consider themselves descendants of Ollman’s curatorial bloodline. The three collaborate with each other as siblings might—staging shows and tackling art fairs together. This is the type of family Adams believes in: the kind where ideas are shared and everyone benefits.

For the gallery’s 10th anniversary, Adams prepared an encyclopedic group show—which also doubled as the first time that all of her artists found themselves in the same room. She had staged an abridged version of this anniversary exhibition at Felix Art Fair a week earlier, but that night, in Adams and Ollman’s glass-fronted space, there was finally enough room to present the community that Adams spent the last decade forging in all

its richness. There was a Joseph E. Yoakum landscape and a Bill Traylor image of a mustachioed man safely distanced from Kinke Kooi’s outstretched octopus arms. A large Jessica Jackson Hutchins sculpture of a jointed ceramic figure slouched over the back of an armchair at the center of the proceedings.

Portland wasn’t in Adams’s initial plan. Born on the East Coast to working-class parents, she remained in Philadelphia after school, ending up at Ollman’s prestigious but unassuming gallery by chance. In her three years there, Adams made herself essential—so much so that when her husband accepted a job in Nike’s Portland offices, Adams joked that her only option was to open Fleisher/Ollman’s West Coast outpost. In a way, she did—affixing her mentor’s name to her own and carving out a space in the city for artists who hunger for a sense of family.

Among those in attendance at the gathering was figurative painter Katherine Bradford, who first met Adams when the gallerist was a student in her class at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Their relationship blossomed when Adams made the move to Portland to open her gallery, and exhibited Bradford’s work for the first time a year later. Another show soon followed, and the two have worked together closely ever since. “It’s really important to me to belong to a group of people that are fun, kind, supportive, and interesting to be with. It’s just the way I wanted to be as an artist, and that’s not what you’re going to find at all galleries,” Bradford says. “When Amy and I are together, we laugh.” Since 2013, Adams has placed Bradford’s work in esteemed institutions including the Brooklyn Museum, the Portland Museum of Art, and the Menil Collection in Houston. The artist gives Adams a lot of credit for her overdue recognition: If a rising tide lifts all boats, then Adams is the ocean. Likewise, her gallery operation isn’t simply a business venture—it’s a lifeline tethering like-minded makers, no matter where they reside, to a cozy idyll on the Pacific coast.

BY KAT HERRIMANAmy Adams braved a historic blizzard to dig out her snowed-in Portland gallery, where she gathered longtime friends and collaborators to celebrate the 10th anniversary of Adams and Ollman.

IT HAD BEEN NEARLY THREE YEARS. Three years of being his wife, of being celebrated for how “well” we showed up in the world. Three years of being praised for our union, a model of “what was possible” for many people in our small, midwestern, Apostolic Christian community.

We met in our sophomore year of college. He told me within weeks that I was the woman God said would be his wife. I relished the idea of being chosen by a man I found so incredibly kind and beautiful. To this day, I’m not sure if there is anyone I’ve laughed with more.

But as my marital fantasy unfolded, a feeling of uneasiness began to seep in. Even before things became serious, my gut—that unnerving, visceral voice inside me—told me that he was a good man, but that didn’t mean he was a good man for me.

The feeling persisted. I wrestled with it over days and nights, feeling anger towards it, trying to pray it away. I even shared it with him, hoping he would say something that might dissolve the boulder of shame and frustration in the pit of my stomach. He said that he felt certain enough for the both of us. I depended on that. But the feeling stayed with

me on that joyful night after Sunday dinner when he proposed to me in his father’s living room. It stayed as we looked into each other’s eyes and said “I do” at the county courthouse. It stayed with me through family vacations and holiday meals, through sweet evenings together by the fireplace in our new home, through the daydreams we’d share about our future children.

The feeling stayed with me right up to the moment—nearly three years into our marriage—when I looked into his eyes again and let him know I had to leave. The fact that I didn’t feel grounded in, passionate about, or deeply committed to him was a sign that he wasn’t receiving what he needed either. Somewhere in the world was a woman who would feel absolutely certain about him. Staying in the marriage was not only dissolving me, it was hindering him, someone I cared about, from finding the things he deserved.

I was terrified. I found it difficult to reckon with my identity outside of my marriage. I was also reeling from the adrenaline rush of self-confirmation that filled my body the moment I left our shared home for the last time. As I drove down the highway at 80 miles per hour toward the house

where my grandmother would hold me in my grief, I felt an unrecognizable relief me. It was explosive and allconsuming—not so much joy, but a recalibration.

As women, we are taught not to trust ourselves, and to believe any voice besides the one that knows us best—our own. We are destined to become an amalgamation of what others think we should be: a mother, a lawyer, a “lovely daughter,” perhaps even a mistake. This ancient societal framework leaves us with little room to chisel out a self that we define.

It reminds me of an adage that I’ve often been told: women used to “be more loyal back in the day.” I cringe at the suggestion. “Back in the day,” women had even less opportunities to assert agency than we do now. They couldn’t simply decide that a marriage wasn’t a good fit—they had to consider what life as a divorcée would mean for their livelihood. While this is still true for many, resisting these expectations was unimaginable before—I certainly don’t believe all women were merely doting wives.

The truth is, my divorce was what germinated my relationship with my courage. I made the conscious decision that doing the hard thing was worth it for my well-being: for the sake

of kindness, for the sake of possibility, for the sake of self.

It has been 10 years since I left. Ten years since we signed our separation papers in the same courthouse where we got married. We shared a meal together afterwards, a soft nod to our commitment to stay kind through the pain. Over these 10 years, the seed of courage that I planted flourished. I nourished it with acts of self-knowing and trust, like my move to the big city, my five-month solo trip around the world, my dive into a meaningful career, my decision to relish in my choice to be child-free. I founded a nonprofit organization dedicated to mental health, wrote a memoir, and continued to pursue my well-being day by day by day.

I often think about the version of myself that stayed. I consider what she might be doing in that parallel universe of choices unmade: the version of me that bent to the pressure to be what so many others desired but just did not feel right. I imagine a wife still living in Ohio, raising beautiful Black children, and celebrating a decade of being married. I think about what that gut feeling might be doing to her as she shares her life with a good man—even though she knows that he’s not good for her.

Ten years after leaving her marriage, the academic and author ruminates on the life she left behind, and the strength and conviction that allowed her to pursue the one she wanted.

Debuting this April in Shanghai, “Gucci Cosmos” brings the Italian fashion house’s rich history to life through interactive installations and rare archival artifacts curated by Maria Luisa Frisa and designed by Es Devlin.

BY DIANA TSUI

That is the question Maria Luisa Frisa was tasked with answering as the curator of “Gucci Cosmos.”

For the theorist and critic, the expansive archive exhibition—which opens this month in Shanghai before touring the world—offers a deep dive into the Italian fashion house’s past and present—and the unique and inspiring ways that they intertwine.

“It’s an extraordinary opportunity to traverse the universe of Gucci and tell its story through the ever-different lens of the clothes, objects, elements, people, and contexts that have made the house an iconic trailblazer,” says Frisa, who worked with artist Es Devlin to spotlight the house’s gift for reflecting and shaping culture over the last century. From the brand’s beginnings as the namesake luggage atelier of Guccio Gucci to its later years under the leadership of visionaries like Tom Ford and Alessandro Michele, “Gucci Cosmos” highlights iconic designs—like the red velvet suit Gwyneth Paltrow wore to the 1996 MTV Video Music Awards—alongside never-beforeseen artifacts plucked from its archives. The exhibition serves as a sweeping survey of the brand’s legacy ahead of the arrival of its newest creative director, Sabato De Sarno, who will debut his first collection with the Italian house at Milan Fashion Week in September.

Debuting at West Bund Art Center in Shanghai, the immersive exhibition consists of eight rooms that spiral backward and forward through Gucci’s creative eras. Devlin is known for futuristic and abstract productions that she has termed “stage

sculptures’’—like the wooden conical Poem Pavilion that she devised for the U.K. Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai, which featured a series of massive poems written through visitor interaction and A.I., or Room 2022, a 7,000-square-foot labyrinth at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2017. The artist applied her unique practice of combining geometric arrangements with audio and visual mapping to Gucci’s archive, creating a cyclical layout for the show that, when viewed from above, resembles a series of interlocking cogs—a nod to the industrial heritage of the Shanghai space.

“Gucci and its history over the past century can be mapped through an ability to evolve and expand on the mutability of our own consciousness, as well as its ability to make cognitive shifts,” says Devlin.

The harmony of Frisa and Devlin’s creative partnership is evident in the seamless alignment of the show’s curation and its design—each gallery tells a story through a mixture of objects, light, and sound. Guests enter through eight revolving doors reminiscent of the years that the brand’s founder spent as a porter at London’s Savoy Hotel. A rotating display of suitcases dating from the 1920s to the present takes viewers on a journey across far-flung locales over the decades.

The next room is an homage to the brand’s equestrian heritage—namely its signature horsebit motif, which adorns leather handbags and shoes and is printed on silk scarves. Flora, a classic Gucci pattern that depicts a romantic tangle of flowers and insects, serves as the theme for the exhibition’s third space, where larger-than-life

creatures taken directly from the pattern are suspended in a mirrored alcove above iconic garments, including a silk minidress from 1969 and Michele’s iconic denim jacket embroidered with the house’s slogan, L’Aveugle Par Amour

As “Gucci Cosmos” winds onward, guests are confronted by two nearly 30-foot-tall statues highlighting Gucci’s penchant for genderless dressing. The space spotlights a number of pivotal design moments, including Michele’s Twinsburg Spring/Summer 2023 collection, in which identical twins modeled matching looks. The next room is for handbag lovers, spotlighting notable pieces such as the Diana, the Jackie, and the Bamboo. Nearby, an enormous cabinet of curiosities display punk-inspired Gucci designs, including a spikeencrusted leather bag, deer-shaped beakers, and a Ford-era electric guitar.

The penultimate display highlights more than 30 Gucci looks arranged by color and inspiration, a manifestation of the brand’s enduring dialogue between modernity and heritage. Drawings by local artists are projected onto a mesh background, a display that links the exhibition to its host city. A final moment of awe awaits visitors at the exit: two large-scale reproductions of the 15th-century Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral in Florence, where Gucci was founded. The brand’s scarf patterns light up the walls, creating a striking kaleidoscopic effect that marks the exhibition’s culmination—a fitting ode to the brand’s origins, and its enduring source of inspiration.

Alexander McQueen · Audemars Piguet · Ba&sh · Balenciaga · Bottega Veneta · Brunello Cucinelli · Burberry · Cartier · Celine · Chanel · Chloé

Christian Louboutin · Dior · Dior Men · Dolce&Gabbana · Fendi · Ferragamo · Ganni · Givenchy · Gucci · Harry Winston · Hermès · John Varvatos

Loewe · Louis Vuitton · Louis Vuitton Men’s · Max Mara · Mikimoto · Missoni · Miu Miu · Moncler · Oscar de la Renta · Prada · Ralph Lauren · Roger Vivier

Rolex · Saint Laurent · Stella McCartney · The Webster · Thom Browne · Tiffany & Co. · Valentino · Van Cleef & Arpels · Versace · Zimmermann partial listing

Valet Parking · Personal Shopper Program · Gift Cards · Concierge Services

Brooklin Soumahoro likens his works— complex, calculated, and painstakingly precise—to bursts of lightning, an apt descriptor for an artist who pours every ounce of his energy onto his canvas.

AT FIRST GLANCE, Brooklin Soumahoro’s paintings appear manufactured. “I want it to be so good, so technically flawless,” he says, “because that’s how I work—like a machine.” But this self-description belies the level of warmth and care that he pours into every piece. “I grew up playing sports, and my coaches would always say, ‘You have to leave it all on the field.’ I need that feeling of leaving it all in the studio.”

The 32-year-old artist works in both large- and smallscale formats but isn’t defined by either: “Size is not a parameter for how much power a work holds,” he says. Indeed, a walk through Soumahoro’s Los Angeles studio reveals works of various sizes in progress, including a series of large oil paintings that he has termed “energy fields.” They consist of multi-colored backgrounds overlaid with intricate webs of fine black lines resembling netting or hosiery and glinting with hints of color. He refers to a series of much smaller colored pencil works as “lightning fields”—detailed linear patterns accentuated with bright bolts of color that explode from their surfaces like trompe l’oeils. This month, two of these massive, black lightning fields will travel to Denmark, where they will be exhibited as part of “Black and White,” a group show at Collaborations in Copenhagen.

Soumahoro, who was born in Paris, has lived in London, São Paulo, and New York, and speaks seven languages—a multifaceted perspective that adds layers of complexity to his work and allows him to tap into expansive modes of thinking. “Traveling around the world and taking in all of those experiences—you put them in your jar,” he says. “At some point, you shake all of that up. I’m interested in perception in painting and perception in life.”

The artist is on the brink of an exciting stage of his career, with shows lined up in Venice, Paris, and Brussels this season. This burst of exposure is the product of very intentional growth; Soumahoro is careful when selecting where he shows his work. “I probably say no to more shows than that I say yes to,” he says. “I ask myself, Does this project sit well with me? ” He applied the same level of introspection to develop his process, which is an extension of his meticulous personality. “I need to be able to enjoy it,” says the artist. “If I’m doing something that I don’t like, I’m not going to last very long.”

BY DOMINIQUE CLAYTON PHOTOGRAPHY BY ZOE CHAIT

515 West 29th Street, New York

Girl on the Grass

Through May 20, 2023

Through meticulous craftsmanship and rigorous studio experimentation, paper, resin, neon, cardboard, and rubber become innovative materials that advance what is possible in contemporary design.

Painting: Aurel K. Basedow. Mixed media and resin

Joy Lights: Draga and Aurel. Neon and resin

Sarcomere Console: Joseph Cleghorn and Connor Moxam. Cardboard, bronze, resin, rubber

Paper Chair №5 and №14: Vadim Kibardin. Paper, cardboard, rice plaster

fernandowongold.com

Misha Khan’s kaleidoscopic Brooklyn studio is bursting with life and color—almost as much as the whimsical furniture he creates inside it. The designer harnesses advanced technology to envision works that surpass even his own imagination, some of which are on view at Friedman Benda this month in LA.

BY ARTHUR LUBOW PHOTOGRAPHY BY ROEG COHEN

BY ARTHUR LUBOW PHOTOGRAPHY BY ROEG COHEN

A GOLD-FINISHED, BRONZE TABLETOP rests on a crinkled pedestal that emerges from a glazed blue boulder. A light fixture ringed by pink shearling hangs in the air like a flying saucer. A couch is composed like a jigsaw puzzle of interlocking, brightly colored biomorphic shapes. With each oneof-a-kind piece he designs, Misha Kahn, 33, gives physical form to the universe that exists in his mind.

“I’m trying to build this whole parallel world through these objects,” he says. “We’re so used to imagery that reflects a skewed vision of our world, but we’re not used to seeing objects that do that. A functional object quickly allows you to imagine other things that exist in that vein. You can extrapolate a whole scene from there, with architecture and vehicles.”

To understand Kahn’s métier, it’s important to know that he stumbled into it. After transferring to the Rhode Island School of Design from a small art college in his native Minnesota, he entered the school’s furniture design program, one of the few majors that allowed transfers. It was at RISD that Kahn discovered his love for designing things that could, at least in theory, be used. “It was really hands-on,” he remembers of his object training, “and very friendly toward making idiosyncratic oneoff things.”

A boyish-looking Brooklynite who lives in Greenpoint and works, flanked by six assistants, in a studio in Sunset Park, Kahn dresses colorfully enough to compete with his furniture. In 2021, he joined forces with the fashion designer Dries Van Noten, who gave the artist a show at his Los Angeles store and collaborated with him on a splashy silk bomber jacket and a T-shirt, adorned with shapes suggestive of internal organs and color-stained like a Helen Frankenthaler canvas. The following summer, he staged his most comprehensive exhibition to date at the Villa Stuck, an Art Nouveau house museum in Munich, Germany, where his dreamy oblong pieces cheerily held their own within boldly patterned and marble-laden rooms. As part of the show, the museum furnished Kahn with a robot that the designer programmed to make paintings in the garden. It is now one of two in his studio—the second robot does three-dimensional carving. Utilizing advanced technology to put a twist on traditional forms and practices excites Kahn; he plans to use the Munich robot to produce an enormous painting for an upcoming corporate commission in New York’s Hudson Yards.

Kahn, who is mounting his fifth exhibition with Friedman Benda in nine years this month in Los Angeles, approaches the labor-intensive

craft of furniture design with the spontaneity of a sketch artist, adopting improvisatory techniques and delighting in the aesthetic paradoxes that emerge as a result. Early in his career, he made a mirror frame by sewing together bags that he filled with yellow vinyl resin. “I was looking for loopholes,” the artist explains. “You see the stitches and the wrinkles from the bag, but you get a liquidy, smooth polish from the vinyl.” Seeking “super immediate solutions to casting,” he crumpled tin foil casserole trays and filled them with wax to create a mold for a one-off bronze work, the crinkly surface of which is about as far as you can get from the hyper-smooth hide of a Jeff Koons balloon dog.

When Kahn first discovered virtual reality software, he heralded it as a liberating means of improvisation. “You can fluidly draw things in V.R., manipulating this pretend clay,” he explains. After using the software to model his designs, Kahn would bring them to life, converting the 3-D files into fiberglass or metal sculptures. At first, the process felt as immediate as crushing tin foil, but eventually he realized he was losing more than he gained. “There was a satisfaction to seeing something so synthetic in the real world,” he says. “But now, V.R. is never the only tool that I use to make something. The first time you see it, it’s magic. Then you see it again, and it’s a party trick.”

These days, when Kahn uses V.R., he no longer renders the original forms it generates. Instead, he blends them with components that he crafts with his hands. Last year, Kahn made a large stainless steel table using digital design software before embellishing it the old-fashioned way. “Seeing the table combined with handmade glass pieces that fit into it is so pleasing to me,” he says. “There’s a tension from this very traditional craft meeting this hyper-digital object. It feels like the next step.”

Kahn’s designs are subversive and uncomfortable—physically and intellectually. His chairs don’t invite you to sink into them, and his tables are unlikely to support a dinner party. “On good days, I feel like I’m getting away with it,” he says. “On bad days, I feel there’s a design crowd that views me as making fringe, non-participatory objects.” Kahn takes comfort in his belief that the boundary between such categories as artist and designer is constantly eroding. “Ultimately, I think people want more and more fluidity,” he says. “The silos of culture take a lot of work to maintain. The next thing on the horizon is obvious. No one cares.”

Misha Kahn’s designs are subversive and uncomfortable—physically and intellectually. His chairs don’t invite you to sink into them, and his tables are unlikely to support a dinner party.

HOW, IN A TIME OF ACCELERATED ISOLATION, can we keep our beloved close? For filmmaker Wu Tsang and performance artist Tosh Basco (formerly known as boychild), the answer was revealed when the pair began playing with translation as an artistic medium. As the story goes, Tsang relayed a story to Basco, which she retold through body movement. This fluid process of call and response eventually led to the formation of Moved by the Motion, a collective of interdisciplinary artists with an ethos of opensource collaboration. The group was born in 2013 from a “desire to work with loved ones near and far,” says Basco, and to create work that “feels like a layering or unfolding.” For Tsang, the visual artist Charles Atlas and choreographer Merce Cunningham’s legendary artistic partnership offered an invaluable roadmap for forming a collective across continents and disciplines. “The beginning felt like falling in love creatively,” she says. Since then, Moved by the Motion’s members have focused on “sustaining that feeling.”

Dubbed “a band” by scholar, poet, and Moved by the Motion member Fred Moten, the collective swells with interlocutors as needed, counting Tsang, Basco, Moten, artist and filmmaker Jordan Richman, dancer Josh Johnson, electronic musician and composer Asma Maroof, and cellist Patrick Belaga as its artist-members. Beyond this constellation is a galaxy of collaborators including artist, writer, and filmmaker Sophia Al Maria and visual artist Kandis Williams. In 2022, Tsang and fellow members presented MOBY DICK; or, The Whale, a silent film adaptation of Herman Melville’s 1851 epic novel. Accompanied by a live score composed by Caroline Shaw, Andrew Yee, and Asma Maroof, a crew of sailors dressed in costumes co-designed by Telfar Clemens embarked on a journey across the high seas, transcending race and gender in pursuit of gelatinous,

glowing blubber. The same year, they dove deep into an equally canonical literary work with their play Pinocchio, a fantastical journey that explores the metamorphosis of a log into a “real boy” through poetry, movement, and virtual reality.

Group work can be emotionally taxing—but for ambitious art-makers, it serves a utilitarian function, too. “Collaboration is essential to the process of making large-scale works,” says Maroof. “It’s never about any singular artist. It takes a village to raise a baby, and that’s what we’re doing here.” For Basco, the process also functions as an act of resistance. “There’s a tendency in the Western world to champion genius and individualism,” she says.

Moved by the Motion is definitively interdisciplinary in its process. The collective disperses each new idea among its members, allowing it to constellate across various planes of expression. For Richman, this process is an art form in itself: a polyvocality emerges as “the boat sails in the wind of the subject at hand,” he says. “We are the whales beneath it, watching and admiring each other’s understanding of that perspective.” For Maroof, the experience is akin to watching a sentence be co-authored. Working off a shared prompt—a novel, a beat, a snippet of choreography— allows the artists to enter a state of creative improvisation. “We start off doing a lot of reading. Then WhatsApp groups form along with playlist streams,” Maroof laughs. “Lots of Post-it notes on the wall, some recordings, wiggles, and giggles.”

Moved by the Motion’s commitment to instinct remakes the everyday as a site of possibility and change. “A lot of our creation happens through trying things without overthinking them,” Tsang says. “No matter where we start, we trust that we will end up somewhere entirely different by the end.”

Moved by the Motion, the multidisciplinary collective led by Wu Tsang and Tosh Basco, explores translation as an art form across continents and disciplines.

“Collaboration is essential to the process of making large-scale works. It’s never about any singular artist.”

—Asma Maroof

FOR 20 YEARS, CHTO DELAT (“What is to be done?”) has been a leading voice in leftist activism in their home country of Russia, making work about art’s revolutionary potential to galvanize the public and activate political change amid persistent threats to freedom of expression. The collective was founded in 2003 by a working group of artists, writers, philosophers, and organizers from St. Petersburg and Moscow, and its work has been exhibited at institutions across the world, including the New Museum, the Centre Pompidou, and the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City. Chto Delat’s members— choreographer Nina Gasteva, artist and filmmaker Tsaplya Olga Egorova, writer and musician Nikolay Oleynikov, and artist and activist Dmitry Vilensky—produce video works, radio programs, publications, and public performance actions that center democracy, workers’ rights, and antifascism with the intention of suturing together art, activism, and theory. While the organization’s name references a 1902 political text by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, it was primarily inspired by Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel of the same name, which Vilensky cites as a guide “for how to construct emancipatory collectives and make them sustainable within a hostile society.”

Stalled revolution is a recurring theme for the group—Chto Delat draws on Situationist theory to emphasize the ongoing possibility of self-actualization amid Russia’s tumultuous political shifts. In Chto Delat’s vision, art cannot be divorced from history or politics— rather, it is a tool to rectify narratives of oppression and give a voice to the marginalized. Its art-actions combine realist, surrealist, and absurdist elements with public spaces—city streets, university buildings—insisting that art’s role in society should not be confined to the gatekept halls of the museum. Its 2022 film installation, Canary Archives, expands on the metaphor of a canary in the coal mine (a warning sign to alert miners of danger) to underscore its members’ resistance to the military invasion of Ukraine. Among its nods to the Russian avantgarde, a modernist art movement that flourished after the Russian Revolutions of 1917, the collective publishes an English-Russian newspaper on issues central to Russian activist culture. The independent press uses manifestos, leaflets, and communiqués as tactics of democratic communication in an otherwise choked media environment. In 2013, Chto Delat opened the School of Engaged Art in St. Petersburg, an incubator that invites newcomers to train

in its philosophy through seminars and group work. The school became a flashpoint for Chto Delat in 2022, when accusations began to swirl that the collective was, in Vilensky’s words, “a training ground for young activists engaged in subversive anti-state activities.” Soon after, police searched the home he shared with Egorova, and confiscated computers, hard drives, and literature in anticipation of a criminal trial. Vilensky, Egorova, and Gasteva sought asylum in Germany, and now reside in Berlin.

For Vilensky, a key member of Chto Delat, group work is a way to resist “individualistic and selfish ideas of artistic genius.” Operating with a Creative Commons license, which allows for the free distribution and use of the group’s work, is a vital tenet of Chto Delat’s commitment to freely transmitting and sharing its message.

“We advocate strongly for free access to our artistic production,” Egorova asserts.

Making socially engaged art requires Chto Delat to function as a “democracy of initiatives.” Any three members can act under the collective’s name so long as the project is presented to the wider group first.

“Everything happens through collective discussion and is based on trust,” Gasteva says. Together, members edit and revise their ideas, accepting disagreement as a part of the process. “Of course, we have conflicts,” says Vilensky, “and whoever has the most passion is the one that wins.”

Through war and censorship, Chto Delat—the leftist, Russian-born collective of artists, writers, and philosophers—demands a revolution for freedom of expression.

SEAN KELLY launched his New York gallery out of his SoHo home in 1991, working privately before opening a public space four years later. His daughter, LAUREN KELLY, and son, THOMAS KELLY, grew up surrounded by the work of art world titans who evolved into an extended family for the young siblings. Now, they are partners in their father’s business—which today represents artists such as Kehinde Wiley, Dawoud Bey, and Candida Höfer.

BY ANNABEL KEENAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY JACK PLATNER

BY ANNABEL KEENAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY JACK PLATNER

FAMILY HAS BEEN AT THE HEART of Sean Kelly Gallery ever since the dealer opened his namesake business in the family’s SoHo home more than 30 years ago. Since then, Sean Kelly’s artists, collectors, and staff have watched Sean’s children, Lauren and Thomas Kelly, grow up—and eventually join the business. Sean claims to have used reverse psychology to get them involved. “I guess it worked,” says Lauren. “I knew exactly what he was doing,” adds Thomas.

When Sean opened his gallery, he and his wife, Mary, had just moved from England with their small children. The art world became a support system for the new arrivals, with a community of dealers, curators, and artists—whom Sean knew from his career curating British museum shows for the likes of Richard Deacon and Antony Gormley—sharing tips on raising a family in their new city. “To us, it was just life,” remembers Lauren. “There were artists everywhere and artwork all over the walls, but as kids, we didn’t know anything else. The art world was both magical and mundane. When we grew older, we became aware that seeing Auntie Marina Abramović whipping herself wasn’t a part of normal life for our high school friends.”

According to Lauren, her professional entrée into the industry felt natural. She joined her father’s gallery after college in 2006, working in various capacities before stepping into her current role as partner. Thomas joined in 2012, leaving behind a career in real estate to help the gallery open its current West Chelsea location in New York. “His ability to oversee large projects and logistics proved crucial,” Sean says of his son. Like his sister, Thomas is now a partner in the family business.

While working as a family may have felt organic, it hasn’t always been easy. “We have all the normal problems one might expect with a parentchild relationship,” says Sean. “Bringing those into a business requires patience and goodwill; we’ve spent so many years working together that we’ve reached an equilibrium. It was well worth it because it brings me great joy to spend so much time with my family. I get to see them grow and evolve professionally and personally. I get to spend time with my grandchildren. I’m very fortunate for this, and I don’t take it for granted.”

His children and partners echo the joy that comes from working together. “He is the most loving and obsessed grandfather I’ve ever met,” says Lauren. She and her brother add that their father’s mentorship has

been crucial on both professional and personal levels.

This tight knit family dynamic also benefits the gallery itself: In an industry notorious for high turnover, Sean Kelly is an outlier. Several staff members have been with the gallery for decades. “The artists and collectors we work with appreciate the continuity as well. They see we are committed to growth,” says Sean. Indeed, the family’s investment in the future offers a sense of security and sustainability to artists searching for a dealer who can be trusted to shepherd their careers. “Being a family impacts the business at every level,” says Lauren. “The artists saw us grow up into, hopefully, mature adults. They know our mother, Mary, who is deeply involved in the gallery, especially on a social level. They’ve seen us start our own families as well.”

Now, these close bonds have led the gallery to expand to the West Coast. Its new Los Angeles outpost, a project that Thomas led, marries the aesthetic of Sean Kelly’s New York location—glass offices with a sleek wood front desk—with breezy California design. The family hired Toshiko Mori, the architect who designed the gallery’s New York location. “We’ve known Toshiko for over 30 years, and trusted her to convey the visual language of Sean Kelly with an LA twist,” says Thomas. Mori collaborated with Hye-Young Chung Architecture to renovate a former yoga studio into the new gallery space. “The decision to open in LA was purely artist-driven. It was to expand our roster and give current artists a chance to create work for a West Coast audience. It’s been incredible to see how the LA community has embraced us, from museum professionals, to other dealers, to collectors,” says Thomas, who moved his own family to the West Coast for the project. “This isn’t a small thing for any of us. My sister gives me a hard time because we are very close, and I moved 3,000 miles away.” This sacrifice is not lost on Lauren. “I do curse him a little,” she jokes. “It’s hard not being in the same city, but it does give me a great excuse to visit.”

The LA expansion is a sign of the gallery’s commitment to the West Coast metropolis—and to the future of the art world during a time of great change. “I’ve been going to LA for decades,” says Sean. “I cannot tell you how many times I’ve been told that LA is the next big thing in art. I always had faith that it would mature into what it’s become, and I’m proud our family is a part of that.”

“As kids, we didn’t know anything else. The art world was both magical and mundane. When we grew older, we became aware that seeing Auntie Marina Abramović whipping herself wasn’t a part of normal life for our high school friends.”

— Lauren Kelly

When WENDY OLSOFF and PENNY PILKINGTON founded PPOW in early 1980s New York, they created a space for marginalized and underrepresented artists to speak out about racism, sexism, homophobia, political corruption, and other prevailing issues of the time. Olsoff’s daughter, EDEN DEERING, became part of the team in 2018, joining the ranks of women she grew up admiring. Now, she is spearheading curatorially-driven programs outside of the new release cycle and welcoming the gallery into its fourth decade.

BY ANNABEL KEENAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY WILLIAM JESS LAIRD

BY ANNABEL KEENAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY WILLIAM JESS LAIRD

“ONE OF THE GREAT THINGS ABOUT BEING A CHILD in the art world is that adults really listen to what you have to say and appreciate your point of view,” says Eden Deering. “Artists see children as peers and treat them with a tremendous amount of respect.” As the daughter of PPOW Co-Founder Wendy Olsoff, Deering counts some of the most talented figures in contemporary art as her friends, including PPOW artists Betty Tompkins, Robin F. Williams, and Portia Munson. Now, as the gallery’s director, Deering works alongside her mother and Penny Pilkington, the fierce duo who founded the organization (the name comes from their initials) in the burgeoning East Village art scene in 1983, establishing a welcoming community that continues to foster experimentation and creativity.

“We were only 26 when we started the gallery, but we knew intuitively that we were creating a path for underrepresented artists,” says Olsoff. Many creatives were flocking to the neighborhood—a notorious hotbed for punk, hip-hop, and graffiti art—at the time, opting for counterculture community over the established art scene of uptown Manhattan. “It was important for us to engage with the East Village and make our exhibitions inclusive,” she adds. “When the community gave us the thumbs up, we knew we had a successful show, even if it wasn’t recognized by the greater art world. In hindsight, working in a vacuum for decades gave us the freedom to construct our own path, showing women, people of color, and LGBTQ artists.” Pilkington and Olsoff instantly set themselves apart from their commercial peers, exhibiting political art and supporting marginalized artists when many would not. They moved to SoHo in 1988, then Chelsea in 2002, and have been in TriBeCa since 2021. After working together for four decades, the two have become like sisters. “That makes Eden one of my favorite nieces!” Pilkington says.

When Deering was born in 1991, the gallery was firmly established with a roster of groundbreaking artists. “I remember spending a lot of time with them,” Deering says, “especially Carrie Mae Weems, who once shot film footage of me and my father dancing; Terry Adkins, whose studio I visited during his artist residency at Dartmouth College; Janet Henry, who was also

my elementary school art teacher; and Bo Bartlett, who I worked with as a model for years.”

Olsoff never expected her daughter to work in the commercial space but always knew she’d end up in the arts. “As a child, Eden was extremely deep, original, and creative, expressing herself in dance and writing,” Olsoff explains. “Her insights were always emotional and compassionate. She wept while watching [Akira] Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai at age 10. I am not making this up!”

Deering did eventually enter the art world, interning at PPOW as a college student before working at Christie’s and then Gladstone Gallery. She also helped launch Duplex with friend Sydney Fishman to support emerging artists and provide a platform to experiment freely, a venture Deering is still involved with today. In 2018, she decided to formally join PPOW. “It became clear to me that I wanted to support and be part of what PPOW was doing. I genuinely felt connected to their program, politics, and important legacy,” Deering says. “Wendy and Penny are strong, independent, empathetic, and ethical people. I love supporting what they have built and continue to build upon.”

Since joining PPOW, Deering has helped usher in a new chapter, spearheading the program of its second TriBeCa location, which opened next door 18 months after the gallery first entered the neighborhood. “With our main gallery committed to nine shows a year, we realized we needed more space,” Pilkington explains. “Eden’s ability to curate great exhibitions and her interest in bringing on new artists gave us the confidence to double in size. It’s wonderful to see Eden build on PPOW’s history and help navigate our path into the 21st century.”

Indeed, both of PPOW’s founders express how grateful they are to have Deering as a part of the gallery’s future, crediting her with their continued growth. Deering, for her part, gives the credit back to her predecessors. “Penny and Wendy are never afraid of change and are always open to new ideas,” she says. “That’s what made it possible for us to celebrate the gallery’s 40th anniversary this year.”

MITCHELL-INNES AND DAVID NASH were uniquely positioned to start a family business. As former heads of the worldwide Contemporary and Impressionist & Modern Art divisions of Sotheby’s, the pair has extensive experience working with blue chip artists. When they transitioned into the realm of private dealing, their years working in the secondary market proved crucial to understanding how best to nurture artists’ careers.

It was Mitchell-Innes that left the auction house first in 1994 and began to work with the conservatorship of Willem de Kooning, who had a body of work and no dealer. “I had two young children, Josephine and Isobel, and the job at Sotheby’s required a tremendous amount of travel. I felt it was best to start my own business,” she recalls. David followed suit two years later, and the pair started their gallery that August. “It was a big risk for us,” he says. “The business was either going to be a huge catastrophe or a great success. We’re lucky and grateful it was the latter. I was very happy to have Lucy lead me through the early years of learning how to be a private dealer.” After de Kooning died in 1997, Mitchell-Innes & Nash was pivotal in valuing his work, and the estate of Roy Lichtenstein soon followed. The gallery spent the next several years working exclusively with artist estates. “We created something of a cottage industry,” continues David. “We were particularly qualified for the processes involved, which are complicated and technical, and we had a lot of experience establishing steady markets with longevity in mind.”

The gallery’s strength with estates firmly established Mitchell-Innes and Nash as a leading name in the secondary art market. As their business grew, the two founders increasingly brought their business—and their interest in other cultures, including Egyptian and preColumbian—home with them. “My parents have always loved collecting from different cultures and periods,” says Josephine (“Josie”) Nash. “Art is what I’ve always known As a child, it was hard to under-stand that was an exceptional thing. Growing up, my sister and I knew that the gallery was a place of business, but we definitely wreaked a fair amount of havoc there.”

In the early 2000s, Mitchell-Innes & Nash started working with living artists, a program that Josephine has become pivotal in growing since she joined the gallery in 2011. She has worked to expand the program and added younger and emerging artists to the roster, including Yirui Jia, Marcus Leslie Singleton, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden. Josephine, who began as a gallery assistant before eventually becoming a partner and senior director, previously held jobs in and outside of the art industry—including a stint traveling around the world to meet with politicians and public figures as the assistant to a prominent

journalist. “Art and the family business have been at the dinner table my entire life, so it made sense to try it out,” she explains. “I never left.”

Collaborating with her parents professionally has been rewarding for Josephine, a sentiment that her parents share, too. “I think everyone understands how comforting it is to spend time with people who have common interests,” MitchellInnes says. “I am excited to get on my hands and knees in a remote garage to discover a work of art firsthand and subsequently sell it to a major New York institution. That could seem odd to some people, so it’s nice that my family understands.”

Josephine’s parents may have started the business, but she has helped grow the gallery’s contemporary vision. “We couldn’t be happier that she enjoys what we created,” Mitchell-Innes says. “It’s also been rewarding to see how she’s grown. It’s hard to explain what it takes for a business to evolve and succeed. Josie just gets it. I am proud that we have increasingly come to rely on her to lead us.”

BY ANNABEL KEENAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY WILLIAM JESS LAIRDSince 1996, husband-and-wife team DAVID NASH and LUCY MITCHELL-INNES have shaped their gallery program into one of the most respected in the city. With the help of their elder daughter, JOSEPHINE NASH, the pair are expanding their contemporary program as they look toward the future.

Influenced by the Neo-Expressionist work and adventurous spirit of her father, Chiara found her own winding path into the art world. Now, the documentary filmmaker has embraced the role of portraiture— a format she inherited from Francesco— in her own creative practice.

BY MAX BLUE PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEREMY LIEBMAN

BY MAX BLUE PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEREMY LIEBMAN

FOR PAINTER FRANCESCO CLEMENTE and his daughter, documentary filmmaker Chiara Clemente, intimate portraits have always been a central part of art-making. But how has the pair’s relationship influenced their identities and individual practices? Francesco’s nearly surrealist watercolors and oils present strange characters and dream-like scenes laden with rich symbolism. He is also known for his stylized portraits of fellow artists, a theme that is the central focus of Chiara’s practice. Her films, which she likewise refers to as “portraits,” are poetic narratives grounded in an equally strong aesthetic sensibility. The father and daughter’s close bond has resulted in a shared ethos—a kindred approach to looking at people and the worlds that they inhabit.

A native Italian, Francesco spent his 20s traveling extensively in East Asia before settling in New York in the early 1980s, where he raised four children. He rose to prominence in that decade as a member of Transavanguardia, a movement defined by the rejection of Conceptualism in favor of a return to Figurative art and Symbolism, blending a Neo-Expressionist style with the in fl uence of Indian religious and folk traditions.

As a result of her father’s work, art has been the main character in Chiara’s life story. The filmmaker, Francesco’s eldest child, was 5 years old when the family moved from Rome to New York, where her father set up his painting studio in their downtown loft on Broadway. “We grew up in the middle of everything,” Chiara says of her Greenwich Village upbringing, “which was a great inspiration for my own work.”

Dinners at the Clemente house involved a rotating cast of artists and intellectuals from Francesco’s close-knit community. Rather than being sent to bed, Chiara recalls, she and her siblings were invited to participate in the festivities—and these nightly salons proved as influential for her as they did for her father. It’s no surprise, then, that Chiara’s films often revolve around the stories of fellow artists: In her short film series, Beginnings, creative visionaries from Christian Louboutin to Yoko Ono reflect on their early years, and her 2008 feature film, Our City Dreams, offers portraits of fi ve luminaries living

and working in New York, including Marina Abramović and Kiki Smith.

When filming her subjects, Chiara often asks about their early years. “There’s a very natural reaction to the experiences from your youth that influences who you become,” she says.

“When Chiara was a child, a friend of mine used to call her the ‘Daughter of the War,’” Francesco laughs, recalling Chiara’s unorthodox upbringing. “She was next to a funeral pyre in Varanasi, [India], when she was still in her mother’s womb. She climbed the Himalayas on the back of a donkey when she was 8 months old. When we hired a babysitter for Chiara in New York, the woman who came saw our dilapidated loft, devoid of any furniture, and said, ‘Oh, okay! I’ve been camping before!’”

This nomadic sensibility, inherited from her father, proved useful in Chiara’s young adulthood. Much of her early artistic development was defined by a need to cut her own path, first by gravitating toward filmmaking as a teenager, then by traveling extensively—a journey that mirrors her father’s. After graduating from high school, she left Manhattan to study filmmaking at Los Angeles’s ArtCenter College of Design before returning to her birth country, where she landed her first documentary job interviewing the American Pop artist Jim Dine for the Roman television channel RaiSat Art. “I had to travel a great distance in order to find connection and inspiration,” says Chiara.

Francesco sees parallels between the experience of parenting and his own artistic practice. “Waiting is the key,” he says, “waiting for a painting to appear, for a feeling to unfold and surprise, to learn the many truths that make a person. It has been said that children are born with a loaf of bread in their hands. I take this to mean that each child has their own particular destiny, their own inclinations—all we need to do is let them be what they become.”

The concept of waiting for a subject to reveal themselves is one that both Clementes bring to bear on their portrait work. For Francesco, whose interests often revolve around spiritual and symbolic systems, it’s a grounding style that he has returned to throughout his career and into the present. Francesco’s portraits might also be