Making faces at art since 1949

Demons Decolonisation Dance-off Candice Lin Trajal Harrell Frans Krajcberg

Isabel Nolan

Katharina Grosse Touching How and Why and Where 7/F Pedder Building 12 Pedder Street Central, Hong Kong

GAGOSIAN

ArtReview vol 75 no 3 April 2023

It’s complicated ArtReview is all for being popular. It has the popular touch. It can shake hands and kiss babies. Or kiss hands and shake babies. Whatever. ArtReview’s readers say ‘Jump!’, ArtReview replies enthusiastically ‘How high?’ And it doesn’t even do a risk assessment. Of course, popularity in art is a more complicated thing than showing how high you can jump. Which is why ArtReview’s mission has always been to make the unpopular popular, and at the same time question whether or not whatever art that is popular should be less popular. ArtReview knows that art isn’t always good just because lots of people like it, nor is it bad because only a few do, and it’s ArtReview’s job to show you, its reader, what might be worth paying attention to, even if everyone else in this ‘artworld’ tells you otherwise. As it happens, those different, diverging takes are what bump into each other all through this particular issue of ArtReview. Choreographer Trajal Harrell’s work, profiled by Evan Moffitt, has always been about who dance is for, and who writes its history, particularly when you’re starting out in a city like New York, home to the tradition of experimental dance shaped by the storied Judson Church Dance Theater. Harrell’s criss-crossing of the city’s ballroom vogue culture with the unexpected strictures of experimental dance, and then with other ‘outside’ dance cultures, speaks to how any ‘art scene’, however progressive, can quickly become exclusive and self-repeating, needing ‘outsiders’ to shake it up.

Dance / Off

11

Sarah Jilani asks who the objects being held in European museums are actually for: Western museums argue that they’re keeping items from other cultures for their own good which, as Jilani suggests, is just another way of saying they still think they’re better than everyone else. But as Oliver Basciano discovers, no artwork is safe when you have a mob running riot, as recently happened in Brazil following the defeat of its right-wing populist president Jair Bolsonaro. As Bolsonaro supporters trashed the Oscar Niemeyer-designed government buildings of Brasília, they damaged a sculpture by Brazilian modernist Frans Krajcberg, an artist whose journey, as Basciano discovers, went from fleeing Nazi Europe to fighting the deforestation of the Amazon jungle. Art museums – when they’re not tearing themselves up over whether to send their collections back to the places those objects came from – are also finding that, when it comes to famous artists, the art often refuses to stay in the museum anyway. In her column, Marv Recinto looks at the explosion in art merchandising, as she traces how Jean-Michel Basquiat’s street art-inspired canvases have made their way from the art gallery back into pop culture, ending up on everything from mobile phone cases to poop-proof rugs. And as Paris’s Musée Picasso relaunches, in a bid to be more appealing to younger audiences, J.J. Charlesworth argues that while museums stress out about making old art accessible, younger audiences are getting their art- and Insta-fixes by flocking to the new wave of ‘immersive’ digital art experiences. Immersed in demonic smells and coated in lard, Rachel M. Tang enters the intoxicated installations of Candice Lin to share some meaningful glances with cats, plague bacteria and sex demons. What she finds is a troubled and surprising web that connects us all, one that suggests that maybe all this isn’t just for our own pleasure, and art isn’t exclusively for humans. If we’re thinking about popularity, why not consider the most populous cohabitants of our planet? Maybe the bacteria have different ideas about who art is for. ArtReview

Man has no understanding

ArtReview.Magazine

artreview_magazine

@ArtReview_

ARAsia

Sign up to our newsletter at artreview.com/subscribe and be the first to receive details of our upcoming events and the latest art news

12

O N V I E W IN AP R IL

NEW YORK

LOS ANGELES

PALM BEACH

LONDON

GENEVA

SEOUL

HONG KONG

Tyler Hobbs Hermann Nitsch Kenneth Noland Richard Tuttle Leo Villareal Louise Nevelson Matta Gideon Appah Kylie Manning Liu Jianhua Saul Steinberg

Zhang Xiaogang pacegallery.com

Art Observed

The Interview Isabel Nolan by Martin Herbert 22 Delicate Spin by Marv Recinto 31

Public/Private by Deepa Bhasthi 32 Making Art Irrelevant by J.J. Charlesworth 34

page 34 Chéri Samba, Quand il n’y avait plus rien d’autre que... L’Afrique restait une pensée, 1997, acrylic on canvas, 81 × 103 cm. Photo: Florian Kleinefenn. Courtesy Galerie Magnin-A, Paris

15

Art Featured

Candice Lin by Rachel Tang 38

Maya Lin by Andrew Russeth 60

Trajal Harrell by Evan Moffitt 48

Universal Falsehoods by Sarah Jilani 66

Frans Krajcberg by Oliver Basciano 54

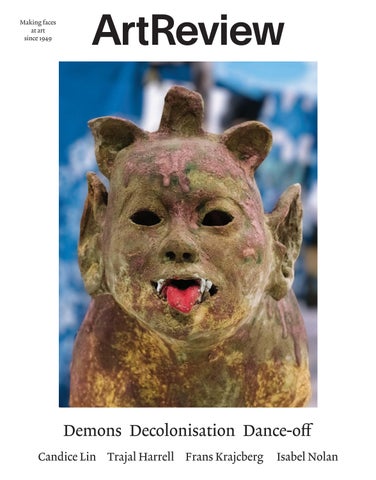

page 38 Candice Lin, Fever Dreams in Quarantine, 2020, underglazed ceramic, 14 × 23 × 19 cm. Photo: Paul Salveson. Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

16

Megan Rooney, Sunday Laundry (detail), 2023. Acrylic, oil, pastel and oil stick on canvas 199.6 x 152.3 cm. Courtesy © Megan Rooney. Photo: Eva Herzog.

Megan Rooney Flyer and the Seed Paris Marais April 2023

Art Reviewed

exhibitions & books 73 Peter Doig, by Tom Morton Georgia Sagri, by Despina Zefkili Tuâ`n Andrew Nguyê˜n, by Jesper Eklund John Kørner, by Martin Herbert Ian Cheng, by Thomas McMullan Swedish Ecstasy, by Padraic E. Moore Liz Magor, by Mitch Speed Nina Katchadourian, by Jenny Wu Kemang Wa Lehulere, by Matthew Blackman Wu Tsang, by Robert Barry Daniel Arsham, by Claudia Ross Aria Dean, by Alexandra Drexelius Ser Serpas, by Cassie Packard Sue Williamson, by Alexander Leissle Chakaia Booker & Carol Rama, by Rebecca O'Dwyer Braving Time, by Tai Mitsuji Balthus, by J.J. Charlesworth State-less, by Wenny Teo Bollywood Superstars, by Mark Rappolt Romantic Irony, by Andrew Russeth

Affinities, by Brian Dillon, reviewed by J.J. Charlesworth Hit Parade of Tears, by Izumi Suzuki, reviewed by Marv Recinto Your Love is Not Good Enough, by Johanna Hedva, reviewed by Chris Fite-Wassilak ok, by Michelle McSweeney, reviewed by Marv Recinto Owlish, by Dorothy Tse, reviewed by Elaine Chiew Space Crone, by Ursula K. Le Guin, reviewed by Kelsey Chen from the archives 110

page 98 Robert Zhao Renhui, Singapore 1925–2025 series, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Mizuma Gallery, Singapore

18

Art Observed

I didn’t come from anywhere 21

Isabel Nolan photographed in front of the Richard Rogers Drawing Gallery, Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade

22

ArtReview

The Interview by Martin Herbert

Isabel Nolan

“One of the things I’m aware of when I’m working is that I’m trying to love the world. That might sound terribly naff, but being alive is strange and hard, and there’s an awful lot of shit going on”

Isabel Nolan’s artistic practice is an expansive one in terms of media, scope of reference and intent. The Dublin-based artist’s formats include painting, drawing, figurative and geometrically patterned rugs, angular metal sculptures, photographs and writing. The cast of characters who populate her work includes metaphysical poets, fictional mobsters,

millennia-old totemic sculptures and our planet’s sun, which Nolan prefers to paint as near the end of its life. That luminary emphasis is appropriate for her constellating model of meaning-making, which combines antiauthoritarianism, a related interest in looking at Western culture in subjective ways to glean new readings from it and a deep ambivalence

April 2023

about humanity, its relationship to the rest of the natural world and our future on the planet, articulated through absurdism and melancholy and compensatory beauty and tenderness. Recently, Nolan took time out from installing her latest show – at Château La Coste, Aix-en-Provence – to discuss how her art’s many moving parts fit together.

23

Don’t Look Up artreview One thing that characterises your work, across its stylistic diversity, is an interest in what one might call ‘downwardness’ – from floor-based sculptures suggestive of chandeliers to paintings of lowering suns, photographs of feet, use of rugs as a medium and beyond. Can you say something about why? isabel nolan I guess it’s to do with noticing a preoccupation with verticality and the veneration of height and light in Western culture. In the history of art, in politics and in religion, power is represented and articulated through motifs that represent ascension or elevation as the ideal state for humanity. It’s in the story of Plato’s cave, of Hades and Olympus, of Hell and Heaven, the Great Chain of Being, even in scientific writing. I felt like every text I would go to, or everything I was looking at, it’s the same pattern always telling me I ought to be impressed by height. Likewise everything that is ‘good’, be it divinity, power or reason, is generally correlated with light. These binaries of light / height are good, and darkness / lowness are bad, seem pervasive. It’s so familiar, it’s easy to forget how strange it is that these metaphors are powerful. They shape the way we understand reality, so introducing contradictory

or oppositional impulses is a way of unpicking these tropes, visually disrupting something generic and positing the lowly, the imperfect and the indistinct as beautiful. It’s different to valorising abjection but probably shares some of the same desire to disrupt, to make space for other ways in the world. ar You seem to practise looking askew. When you photographed the deathbed statue of John Donne in St Paul’s Cathedral [For ever and ever, and infinite and super infinite for evers, 2015], for example, you zoomed in on his knees, and later wrote about their ‘ordinary fallibility… yielding a little to gravity’s sickly pull’. in In part it’s just a response to what I’m drawn to. That statue in some ways looks unremarkable, holy and reverential, but the knees really attracted my attention. They’re a bit bent, quite knobbly, and I thought about them for years after I first saw them. I love cathedrals, though I find their raison d’être very problematic, so finding something like the statue is perhaps a way of mediating or even mitigating my own interest in this stuff. A way of being interested in St Paul’s that’s more complex than simply saying it’s beautiful. I’m not a historian, not a researcher in any kind of systematic way. It’s much more intuitive

For ever and ever, and infinite and super infinite for evers, 2015, archival pigment print, 85 × 122 × 4 cm (framed). Courtesy the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

24

ArtReview

and irresponsible, and hopefully the work communicates that my attraction to this stuff isn’t necessarily predicated on the story it’s supposedly telling us. That other ways of looking at this material and engaging with the culture are interesting and nuanced and suit my own sense of how confused things are, that beauty is complicated. It’s also to do with putting the body back into these histories – or maybe materiality. That statue is very sensual, his lips are so inviting and the folds of fabric between his knees look labial. There’s also an antipathy to dirt and decrepitude, the fact that bodies age and can let us down. It’s often occluded in so-called high culture and made into something disagreeable and shameful. ar You’ve focused, relatedly, on feet numerous times, as in the various photographs of tomb statues’ feet, animals’ paws, thorn-puller statues and pedestrians’ shoes in Curling Up With Reality [2012–17]. in There seems to be an idea that the foot is a rather unpleasant part of the body. I suspect that prejudice is just to do with it being our point of contact with the surface of the world. Take the tradition of foot-washing in the Christian church – it was practical and welcoming, you’ve been walking for days in sandals or travelling on a donkey and your host offers to wash your feet –

Tony Soprano at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, 2017, water-based oil paint on canvas, 70 × 50 cm. Courtesy the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

April 2023

25

Löwenmensch – spanning earth and sky for forty thousand years, 2018, hand-tufted 100 percent New Zealand wool, 15mm pile, 320 × 120 cm. Courtesy the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

26

ArtReview

but it’s also a symbolic gesture, tending their tired, dirty feet is a way of humbling yourself before a guest. Or you know, in ballet, dancing en pointe, it’s escaping gravity – decreasing your contact with the ground is exalted. Metaphorically there’s a powerful connection between the material world, earth, death, horizontality and decay – that’s the realm of feet. In Western painting and statuary I think you don’t see the soles of people’s feet unless someone’s dead. Also architecture rarely invites you to look downward at itself. Surveying from a vantage is different. I thought about it a lot when I spent time in Vienna, it’s such a grand city and people there seem very proud of that, but often the pavements are a mess, which just tickled me. So when I did a show there I made a work that required people to look down. Dogs’ paws I just love. If they’ve been out for a run on grass or sand, their paws smell amazing.

Historical Crushes ar The aforementioned Donne might be considered one of an alternative pantheon, a clutch of figures who’ve shown up in your art, including Paul Thek, Simone Weil, Giordano Bruno and the fictional mobster Tony Soprano, who you painted standing in Vienna’s main art museum, not looking up at its dome. What attracts you to these figures, what connects them? in In some ways they tend to be outsiders, but outsiders shaped by institutions that cannot encompass them or their beliefs, their desire to make a different world. So there is attraction and alienation in the relationship they have to the systems they’re invested in. Their convictions are often strange to me, their commitment is extreme and they went about trying to implement their ideas in very public ways. Mostly they’re driven by a desire to make a better world – but they’re bloody-minded, they annoy people and so often they’re thwarted, yet they live, or lived, with a conviction that’s utterly compelling. Their desire or their beliefs and their world don’t correspond, and that dissonance has a lot of pathos. It’s quite beautiful, the striving in spite of… I think being both recalcitrant and thwarted is important to creativity. Tony Soprano is a bit of an exception. He was the villain in my pantheon, I put him in the Kunsthistorisches museum because he despises art. He’s a psychopath, an arsehole, but incredibly charismatic. From the first episode of the show he’s trying to angrily reorganise the world, his drive and conviction are compelling, but he’s thwarted too, by his anxiety, by his perverse desire for an American dream that’s passed. ar How do you choose, or come to, these people?

in There’s no methodology, I’m drawn to certain subjects and time periods, and to people with belief, scientists too, but it’s largely happenstance. Somebody mentions someone, I read something, and then there’s a lot of invention and projection in the way that I work with the past. Sometimes I read a lot about them or their work but I’m not thorough. It’s often like having a crush, getting excited and preoccupied by a person, imagining all sorts of sympathies with them. They become a way for me to tell a story, or to make something that speaks to the contingency of history. ar The people you focus on tend to be independent thinkers, often falling outside monolithic systems of thought, questioning consensus reality. Looping back to antiauthoritarianism, do you have a sense of where your own comes from? in Hmm. I’ve read a lot since I was very small, and back then I think if you grew up reading, and reading a lot of fiction, you learnt early on that there’s a lot of ways of looking at the world. Growing up in Ireland, the conflict in the north was perpetually in the news. So you learnt about Irish history and colonialism very early on. There was no divorce, no birth control, no abortion, homosexuality was still to be decriminalised. Something like 97 percent of children in the country went to schools run by Catholic religious orders. The church was venerated, though I was fortunate not to have particularly religious parents. Then the cracks appeared, important and devastating stories came out about the church. My mam provided a feminist perspective on things. As a kid she couldn’t get the schooling she wanted, married young, was compelled in so doing to give up her job, had four children and realised that this wasn’t the best deal. She was probably teaching us to read before we could walk. Education was everything at home – she got herself to university in her fifties, eventually getting a PhD. I think it’s that simple. I was implicitly socialised into being sceptical, into knowing that there’s always an agenda with power, another way of seeing.

Remaking the World ar In that respect – looking at historical materials, perhaps rewriting their narratives or bringing out latent aspects – I’m thinking about your recent works involving and invoking an ancient sculpture carved from a mammoth tusk called the Löwenmensch, another example of ‘upwardness’. in It’s a beautiful object, the earliest sculpture that we have from the Paleolithic period, it’s dated to 38000 bce. It’s a hybrid creature, a human torso and legs, and a lion’s forelimbs

April 2023

and head. I’m fascinated by the decision to combine the uprightness of a human and the ferocity, the mentality of a lion. It interests me to think that this is a moment when humans began to remake the world for themselves, and not out of necessity perhaps, but for more abstract or imaginative reasons. A thing that doesn’t exist, someone carves a tusk and now the world is different. That impulse to reformulate the world by physically changing material is fundamental to us as a species. ar You’ve suggested in the past that it relates to mankind separating itself from nature, which could be read as having profound reverberations down to the present. in Looking at it today, it looks like an object that embodies a nature-culture debate, but we have no idea why it was made or what beliefs the maker(s) had. I’ve written about it as possibly predating that Western sense of human exceptionalism, of our special separation from the rest of nature. It seems to join the earth and the sky, the human and the animal. The title of one of my lion-human rugs is Löwenmensch – spanning earth and sky for forty thousand years (2018). But in our preoccupation with mediating the world, many arbitrary distinctions were drawn, and perhaps they were drawn a long time ago. ar You’ve been painting saints recently, and St Jerome and St Paula appear in your current exhibition at Château La Coste. What’s your interest in such figures, beyond their relationship to lions (and lion’s paws)? in My interest in them is more generic than with the aforementioned people. We have the historical evidence and the bonkers elements of their hagiographies, fabulous details like St Columcille prophesising correctly that an inkwell would tip over in the afternoon, or saying that he could see behind himself. Their stories involve making sacrifices, overcoming adversity, successes, falls and ascensions, etc. They follow and feed exactly the same metaphoric veneration of light, height and of course, though I didn’t flag it earlier, masculinity. As figures they also bridge interior and exterior worlds in a way I find fascinating – it’s the thinkers I like. And it may seem archaic but Jerome’s, and the largely forgotten Paula’s, translation of the Bible influenced Western culture profoundly. St Columcille changed the course of British history with the founding of his monastery on Iona. As well as the saints, the show at Château La Coste has a lot of imagery of waves and fish, of microscopic phenomena, passagegrave motifs, figures from Greek myths and dissolving suns, a lot of suns. It relates to something that we haven’t talked about, a preoccupation with the movement not just

27

Desert Mother (Saint Paula) and Lion, 2022, water-based oil on canvas, 70 × 60 cm. Courtesy the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

28

ArtReview

from high to low, past to future, but also from intimacy to vastness – I need pinpoints that allow me to look at long timespans. The paintings and rug are all to my mind set in different eras, the imagery is disintegrating, a lot of dripping paint. I want them to thrum. Space, sky, sea, sun and earth bleed into each other. Then there’s just one sculpture, it’s trying to take up as little space as possible, but still shape the world around itself.

Catastrophising, Drifting ar A long-term preoccupation for you has been extinction, whether in numerous paintings that seem to depict the collapse of the sun at some future point [eg Some time later the sun died, 2014], or even in that sense of a gravitational pull downward in so much of your work. For someone who’s resistant to didacticism, do you think your art engages with ecological issues? in Like a lot of other people, I find what’s happening quite fucking terrifying, and it’s hard not to think about that. But there’s a fantastic cognitive dissonance where, unless you’re an exceptional person, you don’t really change huge amounts of your behaviour, you

travel less, eat less meat and make shows that allude to rising sea levels, future extinctions and the end of the sun. It’s in the work because it’s in my head. And I’ve always had a catastrophic mind, always thinking that the worst is going to happen at any moment. But the work always escapes my expressed negativity – and I find the scope of the universe, the scale of geological time comforting. It puts everything into perspective. I think that shapes the work, the shows; plus there is a pleasure in making, in resisting that negativity by deciding to keep on keeping on. ar Because your work does have those consoling qualities – thinking also of your warm colour harmonies – or is structured on antinomies, as when you shift mediums regularly within a single show, it seems that whatever is there, its opposite can also be found. This could again be related to a resistance to a single way of thinking, or telling the viewer what to do. It feels like, in an exhibition of yours, there’s an open-ended conundrum presented, in which some sort of relationship is being posited between many disparate things, but it’s yours to drift through. in Yes, there are tensions that animate the exhibitions, contradictions testing those binaries I talked about. Maybe it’s partly an attempt at characterising my own experience, which I could

frame negatively as an inability to believe in metanarratives, to be single-minded. I love the word drift, it mimics my way of researching, with the smallest possible ‘r’ that you can put on that. It’s not systematic, more apophenic or something. This thing reminds me of that, connects back to that, and so on… if there’s a worldview, it’s maybe that things are connected. I was writing something very short about Paul Thek recently, it was about dissolving boundaries. And in a way, for me, that’s the work of love. That’s a word I haven’t used yet, but one of the things I’m aware of when I’m working is that I’m trying to love the world. That might sound terribly naff, but being alive is strange and hard, and there’s an awful lot of shit going on. At certain moments when I feel very connected to the world, looking at one of those rare artworks that stop you in your tracks, reading something utterly compelling or whatever, that feels like love. When disparate things start to join up, to make a new kind of peculiar sense, it feels great. There’s something interesting here and some of it we invented it for ourselves, as a way of making being here better, of marking that – sometimes it works. Isabel Nolan’s exhibition 499 Seconds is on view at Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, through 4 June

Some time later the sun died, 2014, watercolour and waterbased oil on canvas, 50 × 61 cm. Courtesy the artist and Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

April 2023

29

Recently I was perusing the Ruggable website. They sell washable rugs that come in handy when you’ve got a naughty pup. Browsing happily through a series of browns and taupes, a sea of jute, the Persian section, the Scandinavian section, the Disney section and the Delphina Delft Blue rug (which looks like a piece of traditional pottery in carpet form), I suddenly recognised some familiar scrawls. My scrolling froze. ‘Is that…?’ I wondered as my cursor hovered over the company’s newest and most gaudy offering. ‘The colours… are reminiscent of a map’, the Ruggable text explains, ‘with a slate blue ocean framing a colourful landmass. Dynamic characters and birds in darker, grounding colours bring an additional element to this striking design. Made from our water-resistant, stain-resistant, and machine-washable low-pile Classic material.’ It was blue with some patches of white and green, and with stick-figure birds that had the look of having been designed by a prison tattooist in something of a rush to render a patriotic collection of bald eagles. This was not, however, the work of an overworked inmate; rather, it was the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Or more precisely, the late artist’s estate. The abovementioned is Ruggable’s ‘JeanMichel Basquiat City Of Angels Blue Multicolour Rug’, a cropping of Untitled (l.a. Painting)’s upper-right corner (1982) that features some of Basquiat’s hit imagery – angels, arrows and blobs of colour. It’s one of 19 options that are either ‘inspired’ by Basquiat, as the website claims, or are direct rug-editions of Basquiat’s paintings. Works like Untitled (Head) (1982), Pegasus (1987), Palm Springs Jump (1982) and Apologia (1981) are literally printed onto these rugs. But others operate in a manner unlike an artwork. You can select a colour scheme to suit your fancy. (Although perhaps you can do that at an art fair, where it’s called a ‘commission’.) You can also choose Basquiat rugs that have multiplied and arranged a square painting into a chequerboard pattern, or that have been picked apart so that choice emblems are enlarged and made into signature graphics for a washable doormat. This ruggery is among the more recent of the seemingly infinite merchandising collaborations that Basquiat has entered into posthumously. The artist died in 1988 at the age of twentyseven; the estate is currently run by his sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux. They are not the architects of these pervasive commercial campaigns, however. No, they passed along all exclusive licensing responsibilities to the consultancy and licensing agency Artestar. While agencies like Artists Rights Society in the us or dacs in the uk will handle licensing agreements (for print, tv and occasional merchandising),

Delicate Spin

What would Jean-Michel Basquiat have thought of the line of easy-care rugs produced in his name, wonders Marv Recinto

Lifestyle view of Jean-Michel Basquiat City of Angels Blue Multicolour Rug. Courtesy Ruggable

April 2023

Artestar seems to have taken this to an entirely new level. Everywhere you look, it’s like Basquiat follows! A Tiffany & Co campaign with Beyoncé and Jay-Z; on the backs of Casetify phone cases people have set on the table while having a pint; maybe someone’s even walking around wearing eyeshadow from the Urban Decay collaboration back in 2017 (hope not, that’s expired by now). In 2021 Artestar founder and president David Stark told Jing Culture & Crypto – a ‘b2b platform covering how Web3 technologies are changing the art and culture landscape’ according to its website – ‘We’re still far from being overexposed like a commercial brand’. While I might disagree – citing the over 25 official collaborations I can count, including Comme des Garçons, Off-White, Funko Pop, nba, Fortnite and Bombay Sapphire Gin – it doesn’t seem like Artestar is stopping anytime soon; in fact, it seems like the company is constantly on the hunt for potential collaborators who, Stark says in the same interview, can tell ‘their story authentically’. The lack of cohesion among existing partnerships tells me, however, that the story is, ‘Let’s make lots of money!’ Which isn’t necessarily a problem. Basquiat embraced celebrity, and the commercial artworld following his inclusion in the 1980 exhibition The Times Square Show, joining first Annina Nosei Gallery then Bruno Bischofberger. Let’s also not forget that his close mentor, collaborator a nd friend was the fame and capitalism-obsessed Andy Warhol. As for licensing today, I look to Keith Haring – Basquiat’s contemporary and fellow Artestar representee – who is perhaps even more ubiquitous than Basquiat in terms of merchandising and was actually Ruggabled before Basquiat. The Keith Haring Foundation deliberately seeks to make as much money as possible to fund its philanthropic efforts, which include supporting underprivileged youth and hiv/aids organisations ‘in accordance with Keith Haring’s wishes’, as is stated on the website. In the case of Basquiat, his intentions for his estate (which notably remains an estate and not a foundation) are not known publicly. Some have wondered whether these commercial campaigns are what he would have wanted: Thom Waite speculated that Basquiat might be disillusioned but also entranced by this omnipresence. He further points out that Olivia Laing wrote, in Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency (2020), ‘You could scorn the commercialisation, but isn’t it what he wanted, to colour every surface with his runes?’ Personally, I can’t pretend to know what Basquiat would have wanted, but I’m certain he never anticipated his works would end up on a washable rug. Had he been around to see the day, however, he might have done what Warhol did to his Jean-Michel Basquiat (1982) oxidation portrait and what my dog will inevitably do whenever my not-Basquiat Ruggable finally arrives: piss on it.

31

The Museum of Art & Photography (map) opened to the public in Karnataka’s capital, Bengaluru, in February with several exhibitions – a survey of the photographs of the artist Jyoti Bhatt, a fascinating solo show by the contemporary artist L.N. Tallur, an installation by the British sculptor Stephen Cox, several new commissions and Visible/Invisible: Representation of Women in Art through the MAP Collection, curated by Kamini Sawhney, also the director of map. Joining the handful of private museums in India, map is a welcome addition to the city’s cultural landscape, especially given its location, next to Bengaluru’s government museums, parks and other tourist sights. It catalogues a collection of over 60,000 works, ranging from Mughal, Rajput and Pahari paintings, to Chola bronzes and textiles from across India, calendar art, Bollywood memorabilia, as well as works from modern and contemporary artists such as Arpita Singh, Baua Devi, Nalini Malani, Rekha Rodwittiya, M.F. Husain, Bhupen Khakhar, Jivya Soma Mashe and others. Many of these, and a large part of the photography collection – the most extensive of the museum’s holdings – were donated by the Poddar family. Founded by Abhishek Poddar, himself a collector, the museum’s collection includes some of the medium’s best-known names, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Raghu Rai, Jyoti Bhatt, Dayanita Singh and Gauri Gill. Visible/Invisible derives from the museum’s permanent collection, seeking to give an overall taste of the kind of works it chooses to hold. The premise to the show is an old, much used trope in India, that of the dichotomy between women’s presence as artists and in art, and their near invisibility in public spaces. The show is divided into four sections: Goddess and Mortal, Sexuality and Desire, Power and Violence, and Struggle and Resistance. With over 130 works, it includes works by K.G. Subramanyan, Chitra Ganesh, Pushpamala N, Somnath Hore, Raja Ravi Varma, Prabhavathi Meppayil and Mrinalini Mukherjee. Alongside are film posters, old advertisements, lithographs, studio portraits, embroidered objects and textiles. The show attempts to give the viewer not only a very wide range of art and artforms to look at, and at times to feel (one of several measures the museum has taken to be inclusive, apart from digital initiatives, is to commission tactile versions of artworks, including those by Gurjeet Singh and Akshata

32

Female Gaze

What does it mean to be a woman in India? Deepa Bhasthi visits an exhibition at Bengaluru’s new Museum of Art & Photography that posits some answers

Anoli Perera, I Let My Hair Loose: Protest Series i, 2010–11, archival pigment print. Courtesy map Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru

ArtReview

Mokashi, for this show), but also tries to peel apart the many layers of women’s existence in India. The catalogue essay by Sawhney focuses on the prevalence of women as subjects or makers in art, especially the many roles imposed on them by men as artists, and as consumers of culture. The female figure is a goddess with extraordinary powers on the one hand, yet in homes ‘women have had to struggle for the right to be mortal, complete with the frailties and temptations that every human must necessarily embody or encounter’. In the case of divinity attached to motherhood, for instance in the Jamini Roy painting portraying Krishna with his mother, Yashoda, one wonders where the girl children are. There is Mother India, seen through the poster advertising the cult film of the same name: the idealised woman made use of by the nationalist movement in the early twentieth century, and in later decades applied to women politicians including Indira Gandhi and J. Jayalalithaa, featured here in photographs by Raghu Rai and Jyoti Bhatt, respectively. Over the course of the exhibition, the role of women shifts, from a measure of a man’s honour, courage and strength, to other expressions, independent in thought, sometimes in action too, shaping a language that reflects a desire to step away from male-appointed ideas. These find place in art as textiles, in contemporary installations, in paintings and as text, and mirror aspects of Indian women’s journeys through the ages. Confronting the male gaze in the film posters, lobby cards and Bollywood memorabilia, while the photoworks of Chitra Ganesh, Anoli Perera, Gauri Gill subvert it by choosing what and how to portray the female self; the agency to be seen as sensual, demure, even invisible, as in Fazal Sheikh’s Moksha series (2005); the right to protest, or just the right to be herself, as depicted in Champa Sharath’s Woman with Blue Pants (2004); the pressures of living alongside the social construct of gender; or the acknowledgement of intense, inescapable violence of Arpita Singh’s Shadow of a Chair (1986): familiar themes of a woman’s life run through the show. It is not comprehensive, but then nothing about women’s lives, so rich in nuance and complexities on any given day, can be. Visible/Invisible goes a good distance, however, in sensitively trying to understand parts of subcontinental women’s experiences.

Do people want to look at old paintings anymore? The Musée National Picasso-Paris announced the rehang of its famous collection this month, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death, with a new exhibition design conceived by British fashion designer Paul Smith. Smith has staged Picasso’s paintings (and drawings and ceramics) in rooms redecorated with vivid patterns, dramatic lighting and walls collaged with historical posters for Picasso’s gallery shows and fashion covers from Vogue. ‘Hopefully,’ Smith muses in the accompanying catalogue interview, ‘we’ve managed to put together more of a visual experience, in a way that is interesting for younger audiences… that are not very knowledgeable about the work of this great master.’ You might wonder how looking at paintings by this legendary twentieth-century modernist might not be much of ‘a visual experience’, but then Smith’s point is really about the worry that ‘younger audiences’ aren’t’ very interested in all this old modernist stuff. What, after all, is ‘relevant’ to twenty-first century gallery-goers? But Smith’s intervention is only half the story. Alongside Picasso’s works and Smith’s zingy designs are installed recent works by artists Mickalene Thomas, Chéri Samba, Obi Okigbo and Guillermo Kuitca, works that view Picasso’s works through the lens of cultural debates that, the museum’s curators imagine, are much more relevant to contemporary audiences. Samba’s and Okigbo’s works point to how Western modernist artists (Picasso perhaps most enthusiastically of all) quoted, borrowed and appropriated from African art during the century in which European powers built vast collections of looted and expropriated works. Meanwhile, Thomas’s Resist #8 (Pitcher and Skeleton) (2022), combines images of African-American women from civil-rights era protests, surrounding an ironic cubist-like rendition of a woman taking the pose of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Grande Odalisque (1814), a low-point of Western art’s Orientalist obsession with the exotic non-Western world. Questions of women’s objectification, of the ‘male gaze’ and of black women’s further marginalisation in the history of Western, male, white modern art collide here. ‘We wanted to open up the museum, reach a wider audience and bring in all those debates: on women, post-colonial issues and politics… We wanted to make Picasso relevant,’ the Musée Picasso’s president Cécile Debray explained to The Guardian. These are indeed current debates,

34

Making Art Irrelevant

As the Musée National Picasso-Paris redesigns its display of Picasso’s work, J.J. Charlesworth asks if the search for relevance obscures the art itself

which indict large swaths of the Western modernist canon, Picasso included. After all, it’s easy to see that Picasso ‘appropriated’ African art, starting with his pivotal canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Nor was Picasso atypical of the sexism that coursed through modernist art: idealising the female body was the flipside of Picasso’s lifelong womanising, philandering and emotional cruelty to his partners, the painter once infamously declaring that ‘for me there are two kinds of women, goddesses and doormats’. In the post-#Metoo, post-Black Lives Matter era, museums of modernist art contend with the hostility or indifference of audiences tuned to feminist and postcolonial critiques of Modernism. These radical revisions of how we look at this art emerged around the same Picasso Celebration (installation detail), Musée Picasso Paris, 2023. Courtesy Musée nationale Picasso-Paris, Voyez-Vous (Vinciane Lebrun) and Sucession Picasso

ArtReview

time Picasso himself finally became history: then, they were critical in dismantling Modernism’s unscrutinised assumptions about (male) genius and creativity, and of Western art’s supremacy over that of other cultures. Now they’ve become standard in academe and in commonplace in wider cultural discussions. But the trouble with ‘relevance’ is that while these critiques are important ways of thinking about how art is made, they can only tell us so much about what artworks do in their own right. Picasso may have been a male-chauvinist shitbag, but his paintings are not the sum of their appropriations, nor the unmediated expression of his vices. Yet such preoccupations now dominate how curators think about how to interpret an increasing swathe of historical art, making art ‘relevant’ to today’s audiences by making simplistic connections with contemporary talking points. It’s perhaps why so much art-historical curating now feels like the wilful overwriting of today’s political preoccupations onto the past. The irony of making past art ‘relevant’ to millennial audiences, assumed to be too distracted or self-obsessed to care, is that it can only guarantee that art’s irrelevance, since it can never live up to the demands made of it in the present. Rather than try to explore what might still be valuable about historical artworks, museums become places to catalogue their inadequacies; at which point one might ask why it wouldn’t be simpler to close museums altogether. But millennial audiences are perhaps not so indifferent to what was valuable about old Modernist painters: while the Musée Picasso frets over whether Picasso can still be seen without being freighted with feminist and postcolonial critique, audiences (some of them young people!) flock to the new generation of ‘immersive’ exhibitions – of Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Gustav Klimt and Frida Kahlo, among others – animated video-projection spectacles that bring the work of those stars of the modernist canon into the age of the selfie. Art critics may sniff at this ‘tawdry genre’ (as one British critic put it), but maybe they reveal a public’s enduring enthusiasm for the visual originality of much of the modernist canon. While Smith designs what amounts to an Immersive’ surrounding to counteract the anxieties of curators who don’t seem to know what there is to like about Picasso anymore, Imagine Picasso – The Immersive Exhibition will open in May in São Paulo.

THE INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION OF CONTEMPORARY AND MODERN ART

APRIL 13—16

NAVY PIER

CHICAGO

Presenting Sponsor

signals … 瞬息 瞬息 ⋯⋯ signals signals … storms & patterns 瞬息 ⋯⋯ 風中序 18 March–28 May 2023, opening 17 March 2023 signals … folds & splits 瞬息 ⋯⋯ 展與接 3 June–30 July 2023, opening 2 June 2023 signals … here & there 瞬息 ⋯⋯ 彼/此 5 August–29 September 2023, opening 4 August 2023 Group exhibition curated by Billy Tang & Celia Ho 策展人:曾明俊、何思穎

(Above) Lai Chiu-han Linda, still from 10957 Moons & 30 Elliptical Years (2022). Video Essay. Courtesy of the artist. Para Site 22/F, Wing Wah Industrial Bldg., 677 King’s Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong 香港鰂魚涌英皇道677 號榮華工業大廈22樓 www.para-site.art Facebook/Instagram: @parasite.hk WeChat: parasitehongkong

Art Featured

Before you started messing around with your computer 37

38

ArtReview

Candice Lin’s Infected Mythologies by Rachel M. Tang

April 2023

39

above Witness (Blue Version) (detail), 2019, ceramic, fabric, metal, papier-mâché synthetic hair, plant material, dimensions variable. Photo: Sam Hartnet preceding pages Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping (installation view, The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota), 2021. Photo: Awa Mally

40

ArtReview

During the Black Plague there were Dutch pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela who were in the habit of wearing pewter badges featuring anthropomorphic vulvas and penises, often depicted riding horses and bearing sceptres. They believed that such charms would ward off disease and disaster. Now, these apotropaic genitals serve as inspiration for American artist Candice Lin’s recent phallic and vulvic installation for the Arnaldo Pomodoro Sculpture Prize at gam – Galleria d’Arte Moderna, in Milan. That work combines painted faux-marble columns, textile chinoiserie, chastity belts and glory holes in an elaborate, ritualistic unveiling of Lin’s own reimagined plague talismans. The exhibition is a consummation of Lin’s approach, a commitment to studying material histories married to her sense of humour, which is essential to her practice. Contrary to the classical ideal of the image liberated by the master sculptor from the marble block, Lin reveals the stories embedded in the material itself. “The work is at its best when I let the materials lead,” she tells me. Here in Lin’s hands, metal, silk and scagliola become more than medium; they become illuminated histories of their use, their origins and their movements across time and cultures. Lin’s future relics – her work consists of sculpture, drawing and video, objects ranging from her own indigo-bound pandemic diary of isolation and observation, to a medieval trebuchet flinging lard laced with bone char, to a screen riddled with pestilent chatbot popup messages – bear temporal signifiers that are scrambled and remixed, suggesting that history and its actors are neither linear nor stable. For example, her near-prophetic 2020 exhibition Pigs and Poison, which toured to venues in New Zealand, China and the uk, was conceived of before the covid-19 pandemic, and her 2021 exhibition Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping at the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, was developed during its early peak. Both exhibitions wield hybrid

human/animal images and corporeal sensations to untangle racialised notions of virality and disease. While not a direct response to current events, Lin’s work calls attention to a troubling history of racist conflations of Asian bodies and infection, which seems to continue to draw ever closer. Lin’s work evidences a deep fascination with how the historical can bleed into the contemporary moment, coalescing into a single, cyclical historical timeline in which the events of history recur and fold in on themselves. Lin has since drawn out even more connections through her extensive research practice, mapping an expansive ecology of colonialism, and in doing so also proved her prowess as an alchemist and historian of materials. Like the process of fermentation itself, Lin feeds the seeds of her initial fascinations with raw material until it blooms into a potent visual metaphor for colonialism’s web of commodities and the violence of those productions. The tendrils of this colonial web knot and coil together, for example, in the indigo feline tent in Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping, which began with Lin’s research on indigo as medicine, indigo poisonings on British colonial plantations in India and changes in traditional Nigerian indigo adire eleko cloth during British colonial occupation. These intertwined histories materialised as Lin herself carried out the traditional process of fermenting indigo, pressing, stirring and feeding it, placing her own body within that ecology. Human and vegetal encounters that take place between poison and remedy reemerge in her recent Venice Biennale installation, Xternesta (2022), in which demonic ceramic totems studded with niches interring various potions and serums act as a botanical library and diy medicine cabinet. ‘Tincture drawings’, in which the artist makes drawings under the influence of her own dizzying concoctions of sugarcane, tobacco and indigo, act as companion records to the demonic archive,

Xternesta (detail), 2022. Venice Biennale, Italy. Photo: Dario Lasagni

April 2023

41

offering a kind of surrealist, automatic document of the porosity of speculations, fantastic characters and plots often teeter at the edge of the mind. However, the vegetal matter in the drawings themselves acts fiction, emphasising moments of history’s absurdity and the instaagainst and resists the memory of the archive, as the ink made by Lin, bility of identity. For example, a figure who appears in her work is the of oak gall and rusty iron-water, burns through the paper and often eighteenth-century European George Psalmanazar, who claimed to leaves ghost images. Lin’s work centres this instability and the haunt- be a native of Formosa (present-day Taiwan) and performed his idea edness of the archive, describing her work, when we talk, as a visioning of ‘Asianness’ by smoking opium and speaking a language of his own of “the cloudy shape of the archive, temporarily felt”. invention. The form of Lin’s demon guardians featured in Xternesta Accompanying the drawings, recipes for alternative medicines – come from sketches of a devil idol made by Psalmanazar in his fabrisuch as abortifacients and ‘clairvoyant testosterone’ – are contained cated ethnographic work; the title of the installation comes from the in a handpainted glass book inscribed with the title ‘minoritarian name he gave to Formosa’s make-believe capital city. medicine’. A reference to the capacity Never utopic, Lin’s speculative Lin feeds the seeds of her initial storytelling is bolstered by her knack of plants to produce both remedies and for worldbuilding through uncanny poisons, Lin draws our attention to how fascinations with raw material such preparations were used by the objects and multisensorial environuntil it blooms into a potent visual resistance in the Haitian Revolution, ments. The sheer number of techniques metaphor for colonialism’s web as well as in uprisings of indentured she uses – weaving, ceramics, dyeing, Chinese labourers in the Caribbean. painting, animation, alongside natural of commodities and the violence Indeed, through these human and processes like fermentation, sporing, of those productions nonhuman material connections as pissing – constructs an immersive sketched by Lin, surface historical solidarities between people too. space. Lin’s previous engagement with Saint Malo’s history, Swamp For example, on the handpainted glass tabletop adjacent to the book, Fat (2021), included in Prospect 5 in New Orleans in 2021–22, uses ceramic amphibians have been forged from clay from the swamps of a process called enfleurage to infuse lard with a blend of ‘demonic’ Saint Malo, Louisiana, a historically multiracial Filipino, Indigenous corporeal smells, like shrimp and decaying flesh. Visitors were invited and Maroon community and the first Asian settlement in the United to take this scent with them by rubbing the lard on their skin, a pseuStates. But as the swamplands of Saint Malo literally recede, the doscientific practice of the Middle Ages meant to ward off disease, and mineral record of this community slips away, a fact that is calcified an implicating, sensual act beyond mere observation. Other bodily within the frog vessels that are pried open for dissection on the glass affective states are productive too, in addition to nausea or grief, as the viewers in Lin’s world are also offered moments of respite and tableau before us. As Lin has further turned to crafting mythologies to expand the intimacy. In Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping, the central indigo shelter worlds of her objects, her bigger story about colonial realities and comprised of delicate wearables, painted rugs and ceramic cat pillows

Xternesta (detail), 2022. Venice Biennale, Italy. Photo: Dario Lasagni

42

ArtReview

Sorting the Rats, 2020, oil paint and lard on wood panel, 46 x 61 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnet

April 2023

43

Swamp Fat, 2021, scagliola, ceramic, clay, earth, mortar, and lard infused with custom scent, dimensions variable (installation view of Thick as Mud, 2023, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle). Photo: Jonathan Vanderweit

44

Swamp Fat (detail), 2021, scagliola, ceramic, clay, earth, mortar, and lard infused with custom scent, dimensions variable. Photo: Jonathan Vanderweit

45

Bedroom Licks, 2020, oil pastel, oil and encaustic on linen, 36 × 46 cm. Photo: Paul Salveson

46

ArtReview

offer us a space to metabolise the vast geographic matrix of colonial vessels (microporous containers often used for fermentations), a tv screen is inlaid into a glazed ceramic frame: in the video a hybrid catencounters in which we find ourselves imbricated. At a moment where the artworld is hyper-interested in ecological pig-human demon awakes from a slumber with a feverish desire to exhibitions of fungi and bacteria, there is a risk that we might simply, have sex. Though the demon doesn’t understand the nature of this as Lin puts it, “get lost in the visual enjoyment of unstable materials”. yearning, the feeling leads our demon friend on a kind of perverse Lin’s 2020 show of small paintings, Roger and Friends, at Friends Indeed, hero’s journey to find their lover through time, memory, menstrual in San Francisco, evidences that even when the artist steps back, if blood and shit. In the story’s final act, faced with its own oblivion by for a moment, from her role as storyteller to focus and reflect on the exorcism, and while under the influence of lithium, the sex demon conditions of her own inner world, she is still actively theorising an catches a glimpse of his lover, who, finally, recognises him back. ecological encounter with ‘the other’. Cats, which appear often in Lin’s This story of bodily desire in the spiritual world is a culmination of Lin’s earthly research. I learned work, embody a compelling sense of In Lin’s paintings is an awareness from Lin that the lithium-addled whimsy, familiarity and curiosity to sex demon represents a personificawhich we might affix our ideas about that to love the nonhuman other relationships between humans and tion of a phenomenon documented is to revel in our mutual opacities, nonhumans. Lin’s portraits of her cat by anthropologist Aihwa Ong in and to delight in the glimpses Roger suggest that Donna Haraway’s Asian women working with multinanow-almost canonical The Companion tional electronics factories who would we get of one another, no matter how become seized by demonic possession Species Manifesto (2003) might be differbrief, without demanding more on the factory floor. For Lin, who first ently read if it were centred around our interspecies bond with cats rather than dogs. In Bedroom Licks (2020), learned about these histories from the artists Ann Haeyoung and Roger seems to recoil from an overaffectionate human tongue, while Miljohn Ruperto (who have also made work on the subject), these in At the Death Bed (2020), Roger is seen lovingly observing people in a mythological objects, queer epics of desire encased in sensorial envimoment of profound loss. In Lin’s paintings is an awareness that to ronments, were sparked by an initial curiosity in the studio about love the nonhuman other is to revel in our mutual opacities, and to lithium ceramic glazes, leading her on her own fantastical journey. delight in the glimpses we get of one another, no matter how brief, To meander through these worlds with Lin is to leave with a better without demanding more. understanding of the threads connecting us to each other. “I make art In Lin’s most recent work, Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory (2023), to learn,” she tells me. Though she makes a good teacher, too. ar made for the Gwangju Biennale, visual and narrative phantasmagoria emphasises rather than obscures real-life social, material and Candice Lin’s Arnaldo Pomodoro Sculpture Prize exhibition is on view at gam – Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan, 14 April – 18 June environmental histories. Flanked by workstations and ceramic onggi

Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory (still), 2023, digital video. all images Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles

April 2023

47

Trajal Harrell Who gets to own the history of dance? In borrowing, mixing and adapting postmodern dance traditions, runway modelling, voguing, butoh and fairground ‘hoochie-coochie’ shows, Harrell, a queer Black man from the American South, reclaims dance as a heritage for all by Evan Moffitt

They came from all over like pilgrims to worship at the altar of postmodern dance. Judson Memorial Church was a Baptist ministry catering to a cross-section of New York’s social classes when it opened in 1891, but by the 1960s it had become the stage for a much more exclusive congregation of avant-garde performance artists, including Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton and Yvonne Rainer. At the turn of the millennium, when Trajal Harrell first attended performances there, the legacy of the ‘Judson School’ had attained the orthodox status of a religion. Brown, the only member of the group to establish her own company, trained countless young dancers there in her late style of the 1980s, which emphasised formal and athletic mastery – a far cry from the asceticism of Judson’s experimental 1960s, centred on restrained, pedestrian movements. Harrell was shocked to find the scene so retrograde. The centre for cutting-edge dance in one of the world’s performance capitals seemed nostalgic for its least radical era. A smalltown-Georgia native and recent graduate of performance programmes in Providence, Harrell had an insatiable hunger for dance. When he wasn’t attending performances at Judson, he travelled uptown to the Black and Latinx vogue balls of Harlem. During Fashion Week he marvelled at models on the runway, whose restrained poses had informed the gestures of voguing. “Here it is: this is postmodernism,” he tells me he recalled thinking. And so one night in 1999 he mounted the stage at Judson, set down a cd player and began posing, slowly and methodically, to the 1982 Yazoo track Ode to Boy. It was a repudiation of Judson’s then-popular athletic style. “I thought this was a ‘fuck you’ piece,” Harrell says, but when he finished the performance, the

48

church erupted in thunderous applause. Stunned, Harrell left without speaking to anyone, but he knew he had done something important. That first work, It is Thus From a Strange New Perspective That We Look Back on the Modernist Origins and Watch it Splintering Into Endless Replication, took its name from the last line of the title essay in Rosalind Krauss’s seminal book, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (1985). Harrell’s quotation of a key text celebrating the ‘death of the author’ suggested that dance could only avoid becoming derivative by responding critically to its own past. This was an operation he compares to ‘realness’, the plausibility of a pose or a look in the vogue ballrooms. “I felt that realness brought a critical lens on the idea of authenticity in postmodernism, because there was this notion that there could be an authentic body or a neutral body,” Harrell remembers, referring to the mostly white composition of the Judson scene. The avant-garde movement had been historicised as making dance broadly accessible – centred on everyday, pedestrian movements – when its living legacy had excluded those who, like him, came from different racial or professional backgrounds. By deploying realness, a concept originating in queer communities of colour, he sought to remind his fellow dancers that authenticity is only ever a performance, the success of which is contingent on perceptions of race, gender, sexuality and class that too often go unacknowledged. He was asking who gets to own the history of dance. That question percolated in Harrell’s mind as he staged more performances around New York, slowly shoring up an iconoclastic reputation. In 2009 it took centre stage in the first of a cycle of works

ArtReview

Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (Made-to-Measure), 2012 (performance view, moma ps1, New York, 2013). Photo: Ian Douglas

April 2023

49

that would occupy him for the next five years. Twenty Looks or Paris social outcasts instead of courtly samurais and princesses. “Hijikata is Burning at The Judson Church (S) imagined what would happen if was interested in weakness and vulnerability, and giving represenvogue ballroom dancers gate-crashed the arch-serious Judson scene, tation to people whom society didn’t want to look at,” Harrell says. demanding their rightful place in the art-historical canon. In a succes- He wondered if, instead of training for decades to become a profession of costume changes to an eclectic pop soundtrack, Harrell pranced sional butoh dancer, he could treat the form almost like a voguing category and see how close his imitation down and around a paper catwalk, his limbs Harrell’s quotation of a key could get to the real thing. For his perfortoo rigidly locked to properly resemble mance The Return of La Argentina (2015) – one Brown’s late work but his movements too text celebrating the ‘death balletic to be considered voguing. In 2012, of several works that have reinterpreted the of the author’ suggested that for Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem / Twenty legacy of butoh – Harrell riffed on an iconic Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church dance could only avoid becoming collaboration between Hijikata and Ohno, Admiring La Argentina (1977; La Argentina (Made-to-Measure), Harrell flipped the script, derivative by responding being a celebrated Spanish dancer who imagining what might have happened critically to its own past. had died in 1936), that involved a lacey if Brown and Rainer had hopped on the This was an operation he ‘tango visite’ dress and a pipe-organ score. A Train uptown to attend a ball, travelling Harrell sashayed into the lobby of Vienna’s from one deconsecrated ‘church’ to another. compares to ‘realness’, Three male performers in loose black robes Leopold Museum tenderly clutching a gown the plausibility of a pose or began tracing sombre, minimal gestures to his chest to the eight-bit sound of an a look in the vogue ballrooms that, by the work’s mid-point, broke out in a Atari game. frenzied freestyle, as they pranced in circles, Such works unlatch questions of cultural swinging their arms wildly, taking turns breakdancing and voguing. appropriation by aiming for something apart from, or beyond, the Harrell had not yet concluded his ‘Judson’ series when, in 2012, impression of authenticity. Swapping contexts and genres throws he first visited Tokyo to study butoh. He had long been fascinated into relief any assumptions about who has the right to engage with the highly stylised dance, which developed in the ruins of post- specific cultural forms. Harrell’s riffs on butoh are specific to his Hiroshima Japan. Its founders, Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata, embodied experience as a queer Black man from the American South, stripped the ancient Kabuki theatre back to its basics, portraying opening histories of dance up to new experimentation and play.

50

ArtReview

above & facing page Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (S), 2009 (performance views, New Museum, New York, 2009). Photos: Miana Jun

April 2023

51

Antigone Sr. / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (L), 2012 (performance view). Photo: Whitney Browne

52

ArtReview

This isn’t a particularly novel approach to contemporary art, but in forms not only for himself, but for everyone who desires to move in the dance world, where performers train to master a specific style, it new or different ways. has a profound implication: Harrell’s work reclaims dance as a shared Harrell has since become a fixture of the international biennial heritage from whose categories anyone, regardless of skill, can freely circuit, owing perhaps to his work’s ability to traverse great temporal borrow. In the words of queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz, he is a and geographic distances while requiring little formal training to ‘disidentificatory subject… who tactically and simultaneously works perform. In 2018 the German magazine Tanz awarded Harrell the title ‘Dancer of the Year’. “It was very shocking to me because I always on, with, and against a cultural form’. For the 2016 work Caen Amour, Harrell reversed his eastward considered myself to be a choreographer who was a bad dancer,” he gaze to consider an Orientalist spectacle of late-nineteenth-century recalls. In response, he choreographed Dancer of the Year (2019), a threeAmerica known as the ‘hoochie coochie’ show. Performed by scantily part solo performance that incorporated gestures from butoh, vogue clad women at travelling circuses, most notably the pioneering ballroom and the streets and Baptist churches of Douglas. In one act, American dancer Loie Fuller, it often involved folding fans and Harrell outstretched a single arm as if shooting a basketball layup, and other vaguely Asian signifiers, with angular, stylised movements then two, in a slow yet rapturous hallelujah. These pedestrian movethat recall early modernist dance, albeit decades before the ascend- ments from Harrell’s upbringing are as constitutive of his underance of Martha Graham. “I’m looking at butoh through the theoret- standing of dance as any academic tradition he’s studied. By isolating ical lens of voguing and looking at early modern dance through the and extending them, he makes postmodern dance accessible to those theoretical lens of butoh,” says Harrell. He recalls seeing the hoochie who, like him, have long felt excluded by its institutionalisation. coochie tent at the state fair in his hometown of Douglas, Georgia, “I hoped I could show that anyone could be Dancer of the Year,” he when he was a boy, though his father forbade him to enter. Caen says. The work channelled his belief that dance might live up to its Amour imagines what he could not witness, staging a hoochie coochie democratic promise. Its congregation should be open to all. ar show in the round so that spectators can see dancers – both male and female – change costumes behind a painted screen. This scenographic Trajal Harrell’s 2022 trilogy of works, Porca Miseria, will be presented gesture collapses public and private, backstage and front, in the same at the Barbican, London, on 12–14 May way that Harrell’s work scrambles signifiers of Dancer of the Year, 2019 Evan Moffitt is a writer, editor and critic East and West, high and low culture. Such rever(performance view, Lafayette Anticipations, based in New York sals are essential to the way Harrell unlocks Paris, 2019). Photo: Marc Domage

April 2023

53

Burnt Man by Oliver Basciano

Frans Krajcberg in his Paris studio, 1966. Courtesy Fonds Harry Shunk and Shunk-Kender, Paris

54

From Europe’s bloodlands to the rainforests of Brazil, the late artist Frans Krajcberg witnessed destruction on industrial scales and turned it into eloquent sculpture. In January the violence came for his own work

Frans Krajcberg, Red composition, 1965, plants and pigment on wood panel, 115 × 89 × 18 cm. Courtesy private collection, Paris

55

Frans Krajcberg’s Galhos e Sombras sculpture at Brasília’s Palácio do Planalto, damaged on 8 January 2023 during the attempted coup by Jair Bolsonaro’s supporters. Photo: Mariana Alves. Courtesy iphan

56

‘Structure broken at four points, one element completely separated Disguising his surname and continuing alone, he joined the Polish from support.’ This is the clinical assessment of a wood sculpture by First Army and was posted to Uzbekistan, eventually participating in Frans Krajcberg by the conservators convened by the new Brazilian the liberation of Warsaw, a position that forced him to bear witness to administration. The work was one of many in the public collection the aftermath of the Nazi atrocities. He would later describe desperdamaged by fanatical supporters of former president Jair Bolsonaro ately searching the Polish capital for his family, but finding no trace. as they rampaged through the Planalto, Brazil’s seat of government in Dislocated, with no sense of home, he moved itinerantly across the Brasília, while attempting to force through a coup in January. Galhos e continent, spending months in Stuttgart with members of the former Sombras (Branches and Shadows) is typical of Krajcberg’s use of found Bauhaus school, before landing in Paris, where he met Fernand Léger wood; here the debris from a tree burned by loggers has been painted and Marc Chagall. The horrors of war had left him traumatised, and white and emerges from a similarly hued wall-hung plaque. The a chance to travel to Brazil as a refugee offered a tantalising new start. sculpture, when intact, had a ghostly and melancholic form. Which He landed first in Rio de Janeiro, homeless and sleeping on Botafogo was apt given that the artist spent a lifeBeach, and then went to São Paulo, a city he He worked ‘not only with the hated. Lasar Segall, a fellow East European time using his art in the service of ecology émigré who had arrived in the country and to decry the destruction of the Amazon beauty of nature’s forms, and Atlantic rainforests. That the work was but also with nature that is being decades prior, suggested he take himself to the countryside in the neighbouring state so badly damaged by supporters of the fardestroyed. My sculptures are of Paraná: it was only then Krajcberg found right Bolsonaro – during whose final month as president, December 2022, deforestation like the memorial of the disaster something approaching peace. was 150 percent greater than in the previous The artist’s first nature works were I see, in the middle of which I live’ December – has inspired a new appreciation simple still lifes of Brazilian flora, but by the of the artist’s political impetus. end of the 1950s these had morphed into the darker, more formally Krajcberg, who died in 2017, described himself as an angry man. complex Samambaia (Fern, 1956-58) series, the leaves rendered in dark His art, though beautiful in form and poetic in imagery, was a mani- brooding oil paint on canvas, heavy with shadow and often set against festation of that fury. He was born in Poland in 1921 to a Jewish family, a background of scratchy, messy brushstrokes. These won him plaudits his mother a communist activist, and saw the majority of his rela- and a growing fame, cemented by winning the prize for best Brazilian tives exterminated in Nazi concentration camps. He himself escaped painter at the Bienal de São Paulo in 1951 (Andy Warhol beat him to east, and took a degree at Leningrad State University that combined the grand prize; Krajcberg also won a prize at the Venice Biennale, art and engineering, a pairing that would come in handy when his in 1964), which, in turn, gave him some security. He started to grow later organic sculptures increased in scale and became architectural disenchanted with the idea of representation, however, at which point in ambition. During the 28-month Siege of Leningrad, he managed the seeds of Krajcberg’s almost animist approach to artmaking flourto slip out of the city with his girlfriend, a first love who, as they ished. The idea of painting nature affirms an anthropocentric sepaweaved between enemy lines, was killed in the forests beyond Minsk. ration from it. The artist began to see himself as a cocreator with the

Damage to the Supremo Tribunal Federal building and Praça dos Três Poderes, Brasília, following the attempted coup of 8 January 2023. Photo: Mariana Alves. Courtesy iphan

April 2023

57

Frans Krajcberg, Queimadas (Fires), c. 1980, photographs taken in Mato Grosso, Brazil, 80 × 120 cm each. Courtesy Collection Association des Amis de Frans Krajcberg, Paris

58

ArtReview

natural world; during the 1960s he produced his ‘Reliefs’, oil works that trace the surface of a tree trunk, for example, or stony ground. Abandoning paint altogether he began work on a body of assemblages, gathering together dried vines, stones or logs into a frame. Red composition (1965) is made up of preserved plants painted with deathly red natural pigments on a wood pane. Although these assemblages have a certain gothic edge, this work was essentially celebratory. His relationship with nature was to become far more political however with the construction of Brasília, which is ironic given recent events. After the Oscar Niemeyer-designed new capital had been inaugurated, in 1960, the 2,070km Belém–Brasília Highway was constructed, cutting through huge swathes of previously wild or sparsely inhabited terrain. Krajcberg took the destruction personally, the insult reiterated after he moved to the northeastern state of Bahia during the 1970s, building a treehouse ten metres up in the branches near the town of Nova Viçosa. Here he lived, worked and witnessed the slow clearing and burning of the rainforest by loggers, cattle farmers and gold miners, some operating legally, many not. From then on, he said, he worked ‘not only with the beauty of nature’s forms, but also with nature that is being destroyed. My sculptures are like the memorial of the disaster I see, in the middle of which I live.’ He built assemblages from burned timber, which grew in size and ambition as the situation got worse and illegal logging and mining increased. At a posthumous survey of the artist last year at São Paulo’s Museu Brasileiro da Escultura e Ecologia, the main gallery of the institution was filled with a forest of these works: hollowed-out roots that climbed spiderlike across the concrete floor; trunks, some painted with natural pigments, polished or carved, others left natural and either half decomposed or fire charred, that reached totemically to the gallery ceiling. Each had their own personality, like ghosts haunting the space. The ‘Revolts’ – the term he used for the works made of salvaged, burned forest wood – are the most poignant. Their emotional

resonance comes across not just as symbols of environmental destruction (the most common reading of the work), but because they are inextricably linked to the artist’s family history. Claudia Andujar is another Brazilian Jewish artist whose family perished in the Holocaust, and she has spoken that her yearslong fight for the Yanomami indigenous people was driven by that memory. For Krajcberg, too, the Revolts seem a revolt against and a revulsion for the violence of humanity. ‘I show the unnatural violence done to life,’ the artist said. ‘I express the revolted planetary consciousness. Destruction has forms, although it speaks of the non-existent. I’m not trying to sculpt. I am looking for forms for my cry. This burnt bark is me. I feel myself in the woods and the stones.’ Seeing billows of smoke choking the sky over the forest was, for the artist, to witness fascist destruction all over again. For good measure, he described himself as a ‘burnt man’. The vandalisation of Galhos e Sombras in January was not captured on film, but plenty of other cctv and camera-phone footage documents the ripping of paintings, the smashing of antiques and the destruction of furniture as more than a thousand people rampaged through Brazil’s Congress and presidential palace. It would be easy to assume a mob mentality, to dismiss the far-right supporters as high on fake news and endorphins, but that might excuse what seems a calculated and systematic attack. Like a forest being cleared for agriculture or mining, hardly a square metre of the complex was left unscathed. The Bahian government, which handles Krajcberg’s legacy, has said that the artist would not want the work repaired and would have demanded that the sculpture be left broken; like all his work, a testament to the violence of man. ar Frans Krajcberg, Le Militant, a retrospective of the artist’s work between 1960 and 2000, is on view at Espace Krajcberg, Paris, through 15 April

Frans Krajcberg, Totems, c. 1980, deforestation-charred tree trunks and pigments

April 2023

59

Maya Lin

by Andrew Russeth

The American sees her work as founded on a mix of art, architecture and the creation of memorials, all of which she uses to honour the past and reshape the future

60

ArtReview

Could it happen today, in the political climate of 2023 America? As discourse in the us has curdled a great deal since then. It is easy to the famous story goes, in 1981, a twenty-one-year-old undergraduate picture Fox News host Tucker Carlson oozing condescension and indigsubmits a highly unconventional proposal for a Vietnam Veterans nation, and Republican officeholders rushing to line up behind him. Memorial in Washington, dc, and in a blind competition against In the intervening 40 years, Lin has of course kept working. Now more than 1,400 other entries, she wins. Maya Lin, the daughter of 63 and based in New York, she has carved out for herself something of Chinese immigrants, faces fervent opposition to her spare design – a sui generis position in the us cultural landscape by moving between two long walls gliding into the land, bearing the names of the different but related roles, uniting different disciplines. She sees her American dead – but in 1982 it is installed on the National Mall, and work “as a tripod”, she said during a talk in February at Hongik it makes her a star. University in Seoul, the three legs being art, architecture and memoThe Vietnam Veterans Memorial has become one of the great rials (or “memory works”, as she has also termed them). sacred spaces in the United States. Walking down its path, people What holds those legs together? Classic Lin pieces evince a quiet grow quiet. They use crayons and pencils to rub names onto paper. reverence for the natural world and an awareness of deep history. They leave flowers and other items. They linger. It is not universally They tend to be restrained – her art often involves only a single mateadored, but it is beloved. When the American Institute of Architects rial – and rooted in a functional logic, while exuding a beauty that published a survey of ‘America’s Favorite Architecture’ in 2007, it is tinged by melancholy. came in at number ten. It was the only entry in the top ten to have been In a solo exhibition at Pace Gallery in the South Korean capital that built in the past half-century, and even more importantly, it was the ran into March, Lin presented a few works that map rivers, a recurring only selection that could be classified as an example of minimalism, practice for her. Thousands of tiny steel pins dotted a roughly 3-by-2m expanse of wall, meticulously charting Korea’s and an unusual strain of minimalism at that. facing page Silver Upper White River (detail), This is an unspectacular monument – beneath Imjin and Han rivers and their many tribu2014, recycled silver, 333 × 610 × 1 cm taries (Pin Gang – Imjin and Han, 2022). It sugthe ground but exposed to light, mournful but (installation view, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, ar). gested a closeup of veins and capillaries, a not sepulchral. It invites collective grieving. Photo: Dero Sanford frozen burst of lightning or even a faraway If the process were to be repeated now, it is above Maya Lin with the final design for the hard to be confident that Lin would be able to galaxy. On another wall, thin branches of recyVietnam Veterans Memorial, presented in see her commission through to construction. cled silver showed the flow of the Tigris and Washington, dc, in May 1981, in the company She faced racist attacks at the time, and had to Euphrates, a similar spread of craggy lines of memorial fund and project directors. defend her plan before Congress, but public (Silver Tigris & Euphrates Watershed, 2022). Photo: Bettmann

April 2023

61

Ghost Forest, 2021, 49 Atlantic white cedars, dimensions variable (installation view, Madison Square Park Conservancy, New York). Photo: James Ewart

62

Storm King Wavefield, 2009, earthwork, 125 × 150 × 5 m. Photo: Jerry Thompson. Courtesy Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, ny

63